This topic that has been on my place radar for some time. Taking students outdoors to learn about and from places has been done for centuries, and I did it in many of my classes when I was teaching. In the last thirty years this practice has been formalized and explicitly named as ‘place-based education’ or ‘place-based learning’. It has been widely promoted and adopted, especially in North America and Australia, but also in Japan, Norway, Britain and elsewhere.

Here I consider it as an example of one of the ways that the importance of place is now being explicitly recognized in different fields and disciplines, and note its alignment with the notion of learning through doing that was first articulated about a century ago by the American philosopher John Dewey. An account of its background and origins from an educational perspective, particular how it developed from attempts to find ways to teach children about environmental issues is provided by Greg Smith in “The Past, Present and Future of Place-Based Learning” at Getting Smart 2016.

Definitions and Principles of Place-Based Education

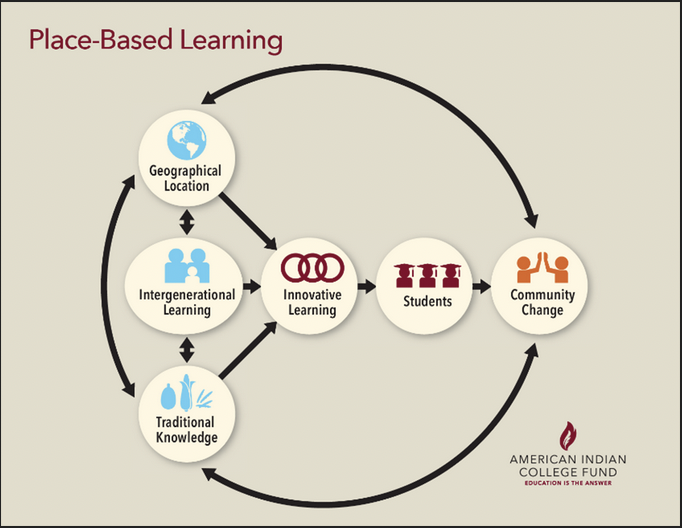

David Sobel, in the first book devoted to place-based education provides a comprehensive definition that is frequently referenced by others : “Place-based education is the process of using the local community and environment as a starting point to teach concepts in language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and other subjects across the curriculum…Hands on, real world learning experiences help students develop stronger ties to their communities, enhance appreciation for the natural world and create a heightened commitment to serving as an active citizen” (Sobel, 2004).

Another more succinct and enigmatic definition, which also seems to be frequently cited, is: “Place based education is anywhere, anytime learning that leverages the power of place to personalize learning” (see: Getting Smart 2017)

These definitions are elaborated in what are often described as the six key principles of place-based education. (See for example: castschool, maine, teton science, and particularly vander Ark et al which is summarized here ).

- A place that is beyond the confines of the school can be a classroom.

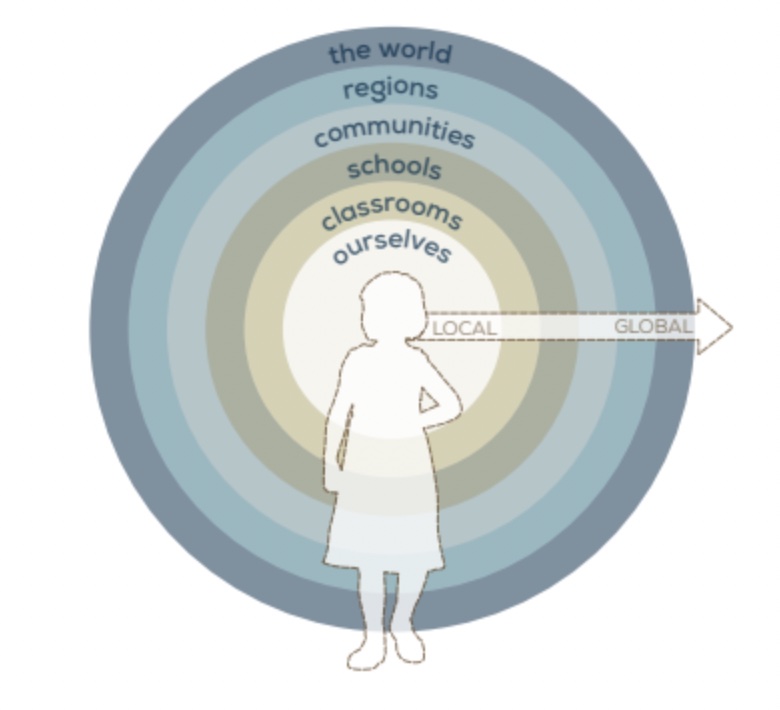

- Local learning can serve as basis for understanding global issues (sometimes phrased as the need to develop a sense of place before trying to understand abstract global problems).

- The process is learner centred, which makes it personally relevant to students.

- Lessons are enquiry based, which involves making careful observations about a place, asking relevant questions, and collecting data in systematic ways.

- Students learn the sorts of critical skills needed to make an impact on the local community.

- It is holistic and interdisciplinary because traditional subject area content and skills are taught through an integrated interdisciplinary approach that responds to real places.

While some of the ideas and practices in these six principles have long been a part of the curriculum, for instance in geography, in place-based education they have taken on a more forceful and focussed role which recognizes that where and how a student learns are as important as what a student learns. Unlike conventional text learning, which is both passive and siloed into subject areas, place-based learning is multidisciplinary, participatory, connects students with a community, and gets them directly engaged in making sense of environment processes and problems.

Place in Place-Based Learning

In place-based education the idea of place seems to be taken mostly as self-evident, unproblematic concept: it is simply a fragment of geography, somewhere local with a particular identity, usually but not necessarily the community or area where the school is located because this is easily accessible. However, implicit in the six principles is the acknowledgement that places/localities are rather more complex than this, that they are the contexts of everyday life, tangled knots of social and environmental features and processes that in various ways are both openings to and open to the larger world, and that it requires some effort of observation and interpretation to disentangle them.

I think the approaches of place-based education are important because they convey to students that we all unavoidably live in places with all their thrown-together complexities, contradictions, and contestations. Places are what we know first in the real world, before we learn about mathematics and language arts and social studies. Accounts and explanations provided by conventional disciplines, no matter how complicated they may sometimes seem, are always simplifications of our experiences of places.

Place-based education is also important because teachers have to educate students in ways that will help their students to deal with what they will encounter in the rest of their lives. It is easy to despair about the unprecedented local and global challenges of the 21st century, including climate change, ongoing degradation of natural environments, and persistent inequalities, but the advocates of place-based learning bring a very positive attitude to handling these. Peter Renshaw (2017), for example, is confident that place-based learning can provide the personal connectedness and interdisciplinary flexibility that are essential tools for dealing with them. And Tom vander Ark, Emily Liebtag, and Nate McClennen are utterly optimistic about the value of learning from place (vander Ark, 2020, p. 132):

“Despite mounting risks, the second decade of the 21st century is a wonderful time to be a young person on this planet. It has never been easier to make an impact by coding, launching a campaign, starting an organization that will have an impact on the world, and many of these will be the result of an adult working with a young person and a place.”

John Dewey: “Local geography is the natural starting point”

In the background of place-based education, and frequently referred to by its proponents, are the ideas of the early 20th century American philosopher John Dewey. He didn’t write explicitly about place but he did argue that schools needed to move away from memorization of received knowledge to experiential learning. In his 1916 book Democracy and Education (Chapter 16, The Significance of Geography and History) he claimed that if geography and history are taught as ready-made studies which somebody studies simply because they are sent to school, it easily happens that “ordinary experience…is weighed down and pushed into a corner by a load of unassimilated information.” On the other hand: “With every increase of ability to place our own doings in their time and space connections, our doings gain in significant content;” in schools, he suggests, “local or home geography is the natural starting point” to encourage this.

Dewey did acknowledge that some content, facts and values had to be taught in classrooms, but his pedagogical philosophy emphasized above all the principle of learning by doing. Abstract knowledge needs to be grounded in activities in the real world. And because education is unavoidably connected to community and social life, this necessarily involved engaging directly with the community and its local or home geography. It took another eighty years for Dewey’s suggestion to be realized, but grounding abstract knowledge is exactly what place-based learning aims to achieve by deriving it from the investigation of local communities and places.

Two Qualifications: Non-Places and Learning from Places

This straightforward interpretation of place as local community and geography, which seems to be assumed by many proponents of place-based education, is problematic according to Joy Berling (2018). She raises the matter of non-places, the ones without history or culture that are described by Marc Augé (1995) in his book about them, and argues that rooting place-based learning in the local environment and emphasizing place awareness fails to address the fact that place is “increasingly ephemeral or even non-existent in the world of supermodernity.” I think this is an important caution. In order to help students makes sense of the modern world it is just as worthwhile to investigate uninspiring, placeless settings apparently empty of culture, as it is to examine conveniently local fragments of geography.

Moreover, if education is understood in its broadest sense as learning about the world, and places are understood as complicated territories of meanings with or without distinctive identities, then it is clear from the insights of numerous artists, poets, philosophers and scientists that there are many ways individuals have learnt from them that owe little to the pedagogic approaches of place-based education. Some that spring easily to mind are Alexander von Humboldt, Gilbert White, Wordsworth, Cézanne, van Gogh, Thoreau, Darwin, Heidegger, even Descartes whose philosophy explicitly disavowed place but nevertheless carefully described the places where he conceived that philosophy. I don’t know that place-based education has much to learn from the place experiences of such remarkable people, but from the perspective of place they suggest some intriguing possibilities that I hope to explore in a future post.

References

Augé, Marc, (1995) Non-Places: Introduction to the Anthropology of Supermodernity, (London: Verso)

Joy Berling (2018) Non-Place and the Future of Place-Based Education, Environmental Education Research, Vol 24, Issue 11

John Dewey, (1916), Democracy in Education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. Available at Project Gutenberg

Peter Renshaw, ed., (2017) Diverse Pedagogies of Place: Educating Students in and for Local and Global Environments, Taylor and Francis, London

Sobel, D. (2004) Place-Based Education: Connecting Classroom and Community, Great Barrington, MA, The Orion Society.

Tom Vander Ark, Emily Liebtag, and Nate McClennen (2020 )The Power of Place: Authentic Learning Through Place-Based Education, Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development