Sometime around 1970 there was a shift in how places were made and experienced that is still evolving. Whether it will amount to the sort of radical change that happened with place practices, for instance when the Middle Ages transformed into the Age of Reason, remains to be seen. What is clear is that there are substantial differences between the ways that places are treated now and what happened before 1970, when little attention was given to history, tradition, community or environmental consequences of development, and places were either ignored or regarded as irrelevant to progress.

I have discussed these recent changes to place in previous posts on this blog, here, here and here. In this post, which considers trends from 1970 to 1990, and the following post, which considers trends since 1990, I review these briefly and add interpretations relevant to the future of places. Because I devote only one or two paragraphs to topics which are enormously complicated I want to stress that my main interest here is in places and the remarkable diversity of social trends that have affected them over the last fifty years.

Environmental Conservation, Sustainability, Ecological Awareness

In the 19th and first part of the 20th century, with the notable exception of the creation of National Parks, natural environments were treated mostly as somewhere for free waste disposal or something that could be improved by engineering – building dams, straightening rivers, levelling hills, using chemicals to kill pests and improve yields. In the 1960s those attitudes came under intense criticism (for instance Rachel Carson’s revelations about DDT in her book Silent Spring) as it became increasingly apparent that from an ecological point of view this was doing immense environmental damage.

The concrete channel to approve flow in this creek in Toronto was constructed in the 1960s at about the same time the Rachel Carson Wildlife Refuge was created in Maine. It typifies the engineering approach to improve environments that prevailed then. The photo on the right shows a section of that same watershed just after it had been renaturalised in the 1990s according to ecological principles in order to prevent downstream flooding caused by concrete channels.

The birth of the modern environmental movement is often held to be the first Earth Day, celebrated across the U.S. in 1970 in popular demonstrations to promote reforms in environmental practices, and now recognised annually in 180 countries. Perhaps more significant for its effects on places was the establishment, also in 1970, of the Environment Protection Agency to coordinate federal government strategies in the U.S. to monitor the condition of environments and enforce policies for conservation. This sort of approach was expanded internationally in 1972 through a United Nations conference in Stockholm on the state of the environment that was held in Stockholm in 1972. This was substantially reinforced in the late 1980s by the UN sponsored the Brundtland Commission that introduced the notion of sustainable development – an approach that considers the consequences of environmental impacts for future generations.

The significance for places of this lies in the fact that ecological thinking is at the root of modern conservation, and ecology requires paying close attention to the particularities of places because ecosystems are expressions of local geological, topographical and microclimatic conditions. Developments that are environmentally damaging and unsustainable still happen, and the sheer scale of urban development needed to accommodate population growth can outweigh good intentions, but since 1970 conservation and sustainability have come to be so widely integrated into plans and policies for places at all scales from neighbourhoods to nations that it is difficult to realise that fifty years ago environments warranted no special attention and policies for environmental protection scarcely existed.

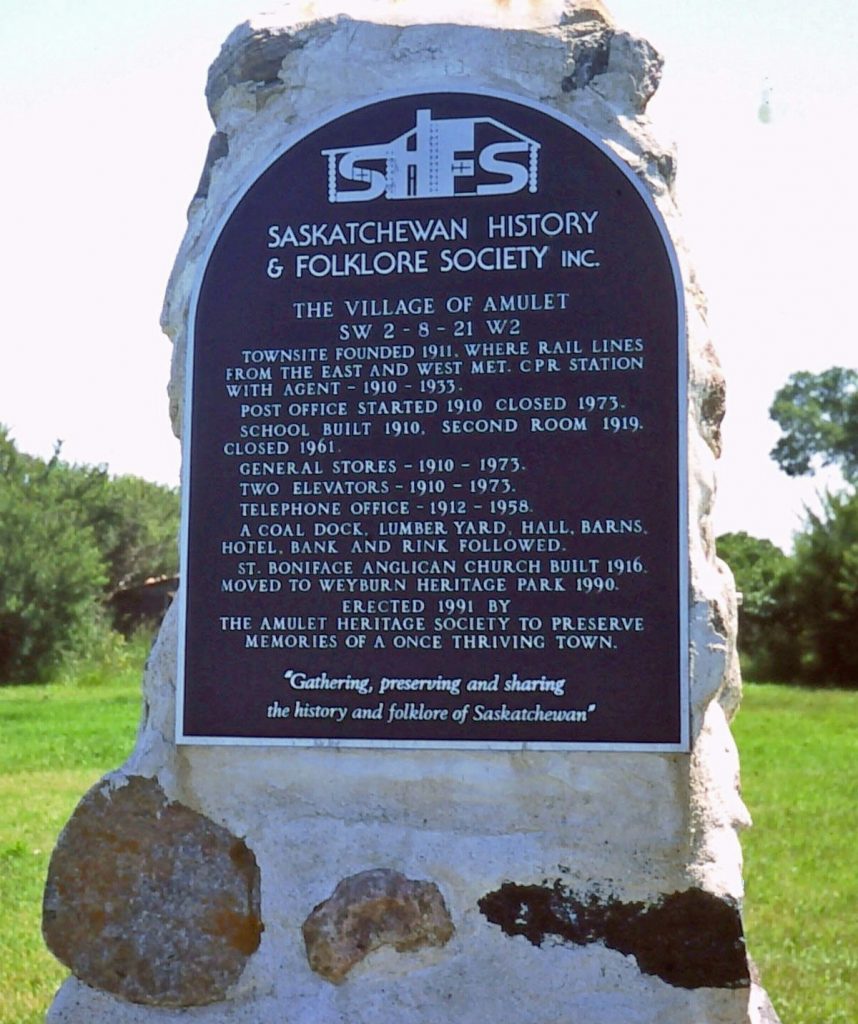

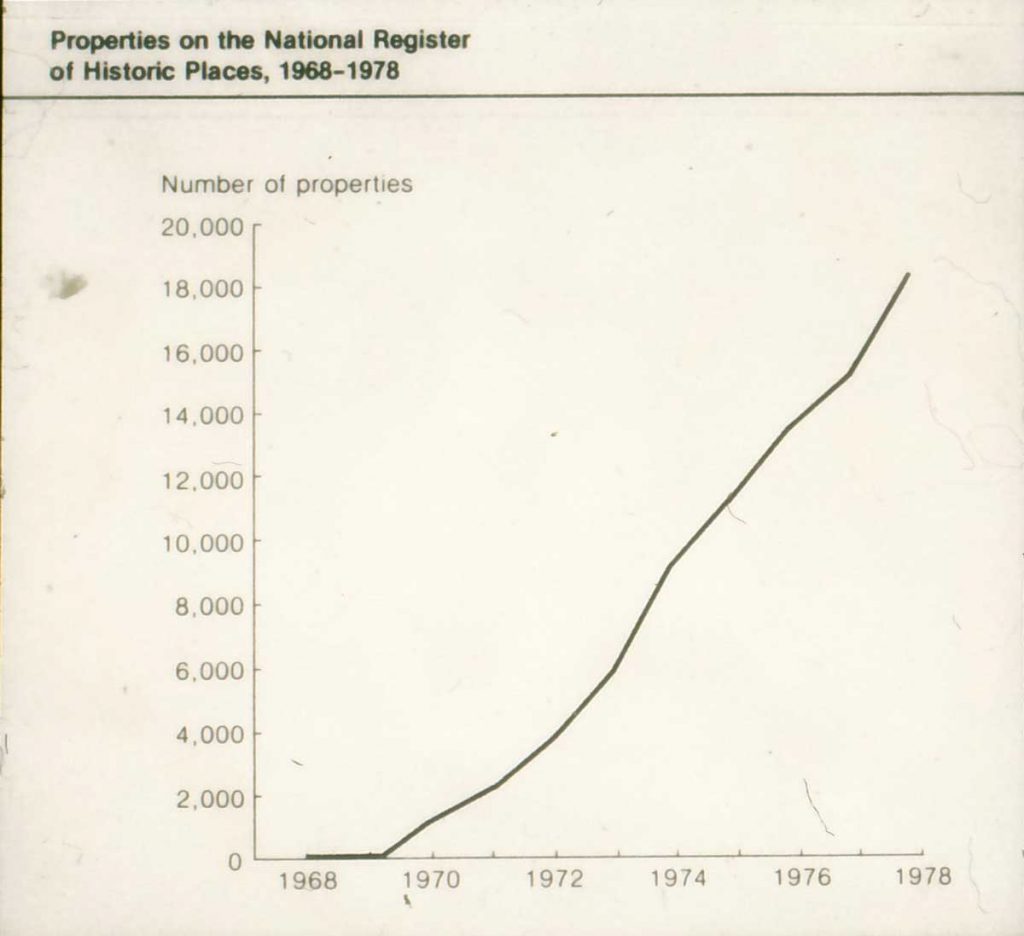

Heritage Preservation.

Growth of interest in heritage preservation to protect built environments was almost exactly contemporary with the rise of environmental conservation. As an international and widespread concern it is mostly an outcome of a UNESCO convention in 1972 on the protection of cultural and natural heritage. This convention led to the designation of World Heritage Sites as a way to protect sites of great cultural significance that are threatened by development, and it actively encouraged individual nations to legislate their own heritage protection policies.

Before 1970 the word ‘heritage’ meant ancestry, and old buildings and districts were regarded mostly as impediments to progress, best removed to allow urban renewal or for economically profitable development. Since then heritage protection has been widely given legislative authority and implemented through local planning practices. It has become a very powerful force for protecting a sense of the continuity of places almost everywhere, from World Heritage Sites (an average of 25 have been added every year, and there are now about 1100), to urban districts and individual buildings that are zealously protected as essential aspects of local history.

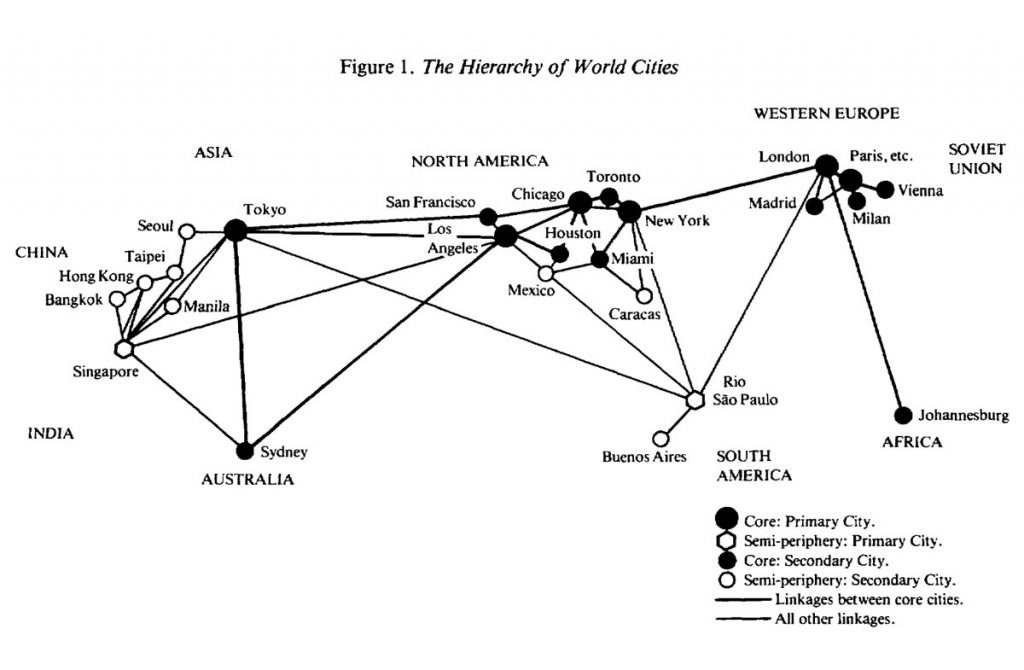

Globalization and Deindustrialization

The effects on places of globalization, which in its current neo-liberal, free-trade form was a response to problems of inflation in the 1970s associated with post-war economies that were based on controls over capital and wages, are less direct and locally apparent than heritage preservation and environmental conservation. One large scale consequence appears to have been the emergence of ‘world’ or ‘global’ cities that act as command centres in the global economy, with offices and institutions monitoring and controlling international flows of goods, people, ideas and money. They privileged places attract wealth and attention, and are characterized by stock exchanges, corporate headquarters, international institutions, hub airports, and, because they attract immigration, ethnically diverse populations. London and New York are at the pinnacle of a hierarchical network of perhaps 150 world cities (whose interactions are thoroughly documented by the GaWC or Globalization and World City research network.) These are in many ways more connected with other world cities by financial trading, cultural activities, airline routes and fibre optic cable, than they are with the regions and nations where they are located.

Another, almost opposite, place consequence of globalisation and worldwide trade has been deindustrialization. Manufacturing has been moved to wherever production costs, especially costs of labour, are lower. This has created new manufacturing zones in less developed nations, and deindustrialized regions and rustbelt cities in developed nations. The latter are disadvantaged places in a globalized world, with closed mines and abandoned factories, and few prospects for sharing in the growth and prosperity of world cities.

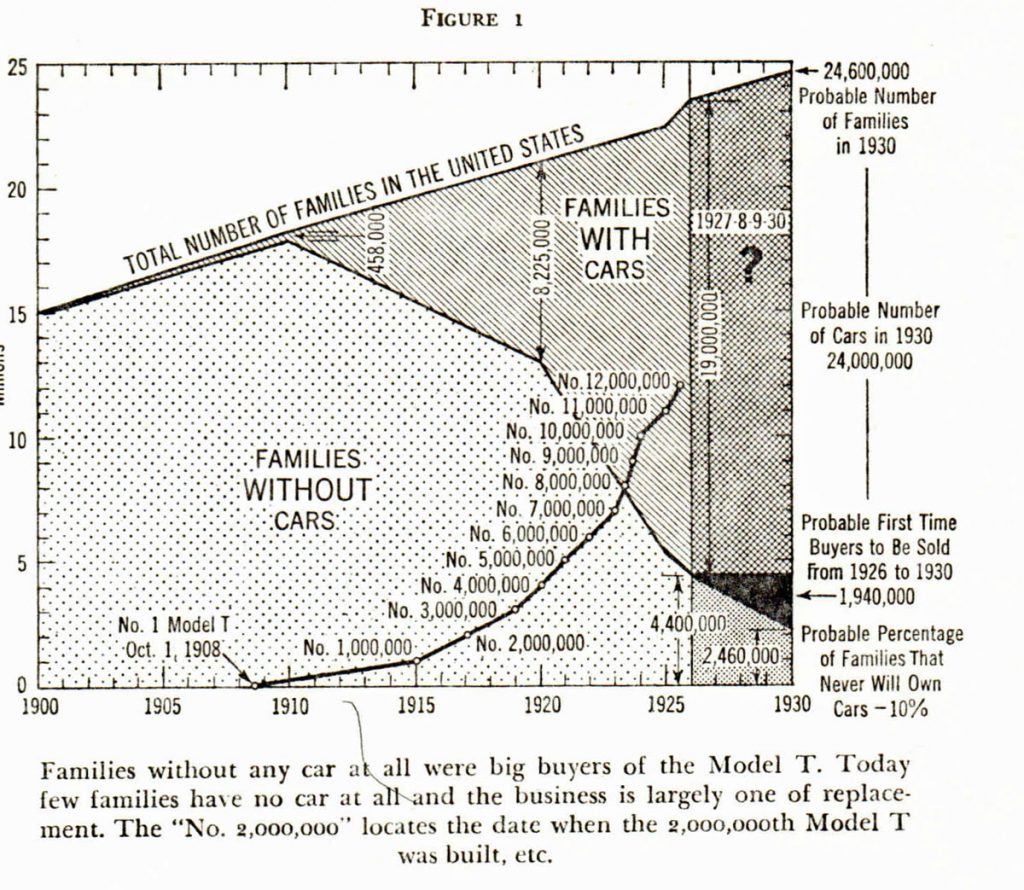

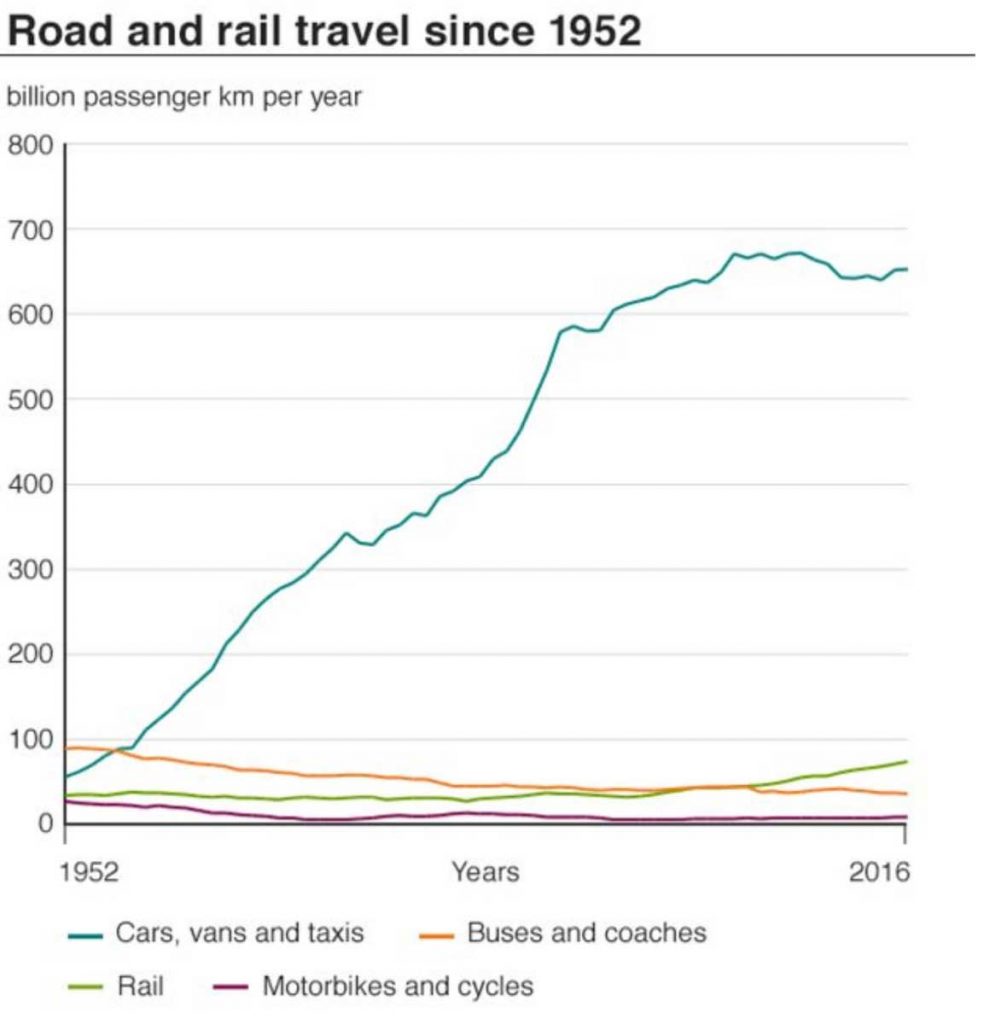

Mobility

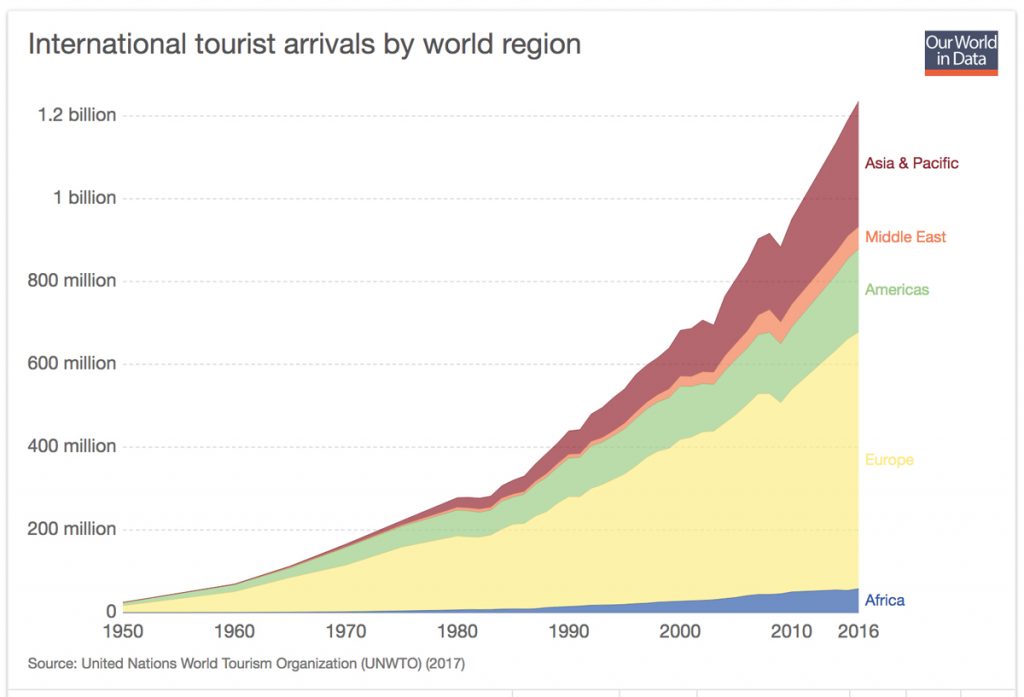

One aspect of globalization has been a rapid increase in international and regional mobility both for business travel and tourism. This is an important change because for much of history most people experienced only a few places in the course of a lifetime, life was about stability and having deep roots. Now the reverse is true – daily commuting, weekends away, vacations in previously remote countries on the other side of the world. It seem that within one or two generations depth of place experience has been traded for breadth in which many different places are encountered briefly. Whether this improves or diminishes place experiences is an open question – it may be relatively shallow but by exposing travellers to different cultures it also overcomes parochialism.

The recent surge in mobility has, in concert with rapid urbanization, stretched urban areas outwards until they connect in sprawling megalopolitan regions (hundred mile cities, as Deyan Sudjic has called them). The built environments of these vast places are formed around a skeleton of expressways, high-speed rail lines, intermodal facilities (where containers are moved from rail to trucks, etc), distribution centres and airports. Hub airports are especially notable because their immense buildings have no architectural or planning precedents, and are the largest single places (or non-places, which I will discuss in the next post) in the landscapes of cities.

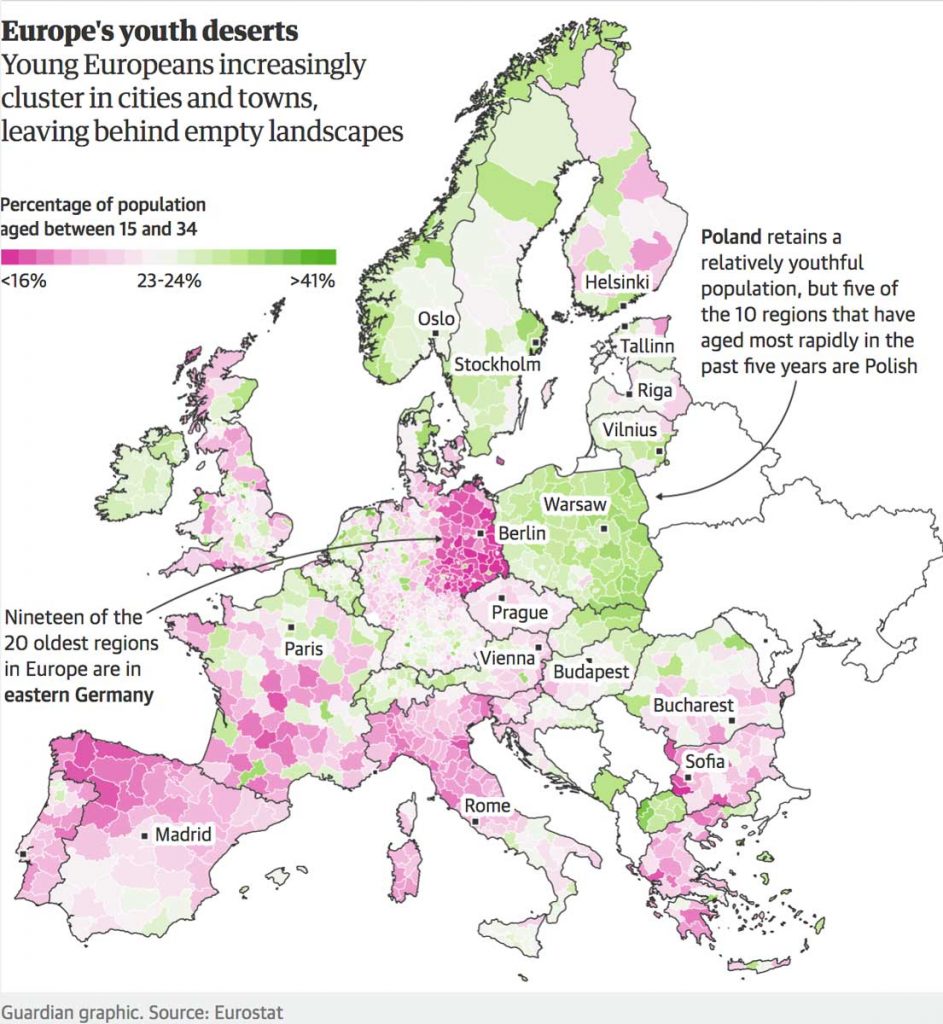

Migration and Hybrid Places

Another form of modern mobility is migration from less to more developed parts of the world where it is needed to maintain population and economic growth. The consequence for places is that new cultures and traditions have been added to the older national ones, especially in world cities that have become especially attractive for new immigrants because they are where prosperity is. Leonie Saundercock in her book Cosmopolis II (2003) refers to these as mongrel cities because such a large proportion of their population (in Toronto, for example, it is over 50 percent) comes from a variety of different countries. Places that in the 1960s could be considered culturally homogeneous have become complex hybrids, filled with people of different races and religions, celebrating their own heritage in festivals and foods (and engendering tensions as local traditions lose their once privileged positions).

This hybridity has a global aspect because electronic communications and relatively inexpensive air travel have allowed the modern diasporas of cultural groups to interact closely both with their homeland and with their transnational fellows in other countries. In effect, hybrid places, no matter how geographically separated, are now closely connected.

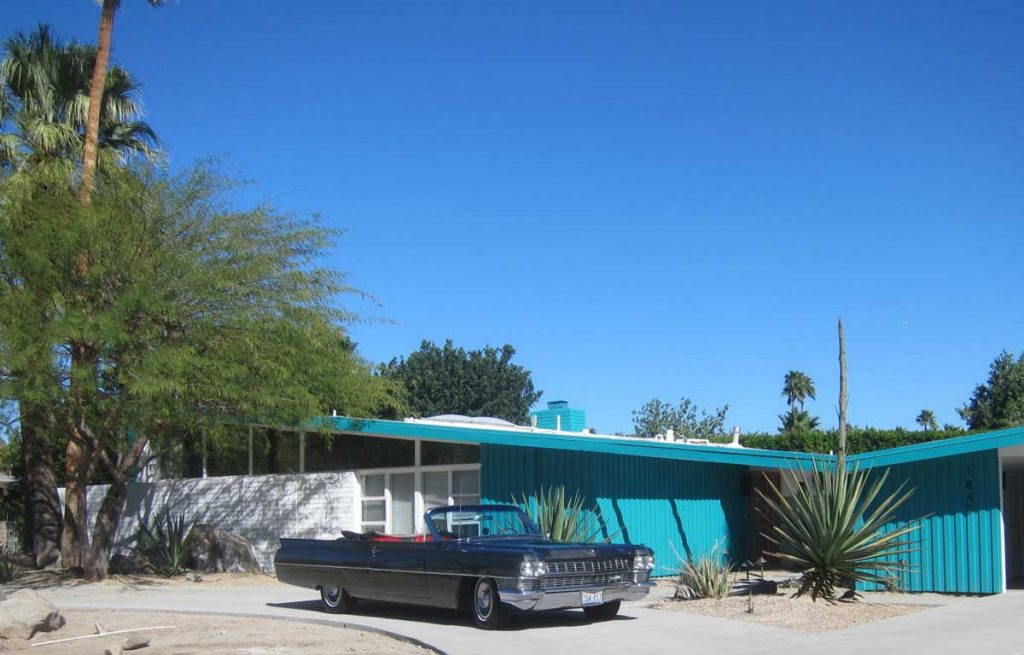

Postmodern Architecture and Planning

In the 1970s architecture and urban planning began to move away from the rectangular, uniform designs of modernism to more decorative ‘postmodern’ forms. In architecture these have involved elements from older building styles, such as pilasters, pediments and colours. In planning it has been manifest in ‘new urbanist’ or ‘neo-traditional’ approaches, a form of master planning that aims to enhance place identity both by responding to local ecological processes, copying local vernacular architectural styles and creating walkable streets,

Postmodern architecture and Planning. Mississauga City Hall, Ontario, from the 1980s was designed to reflect the old farms that once occupied the land (farmhouse in front, windmill tower, barn behind). A new urbanist main street in Garrison Woods in Calgary, built in the late 1990s.

And Postmodern Philosophical Shifts, Heterotopia and the World of Where and When

There is a deeper, philosophical meaning of postmodernism that could herald a fundamental shift in approaches to how places are made and experienced because it implies that the rational way of thinking that has prevailed since the Enlightenment may have run its course. This rational attitude, with its assumptions about the power of reason and objectivity to reveal truth and reality, has informed the development of science, law, economics, technology, political institutions and ways of making places for the last four centuries. But in the 20th century its privileged status came into question, initially in art (abstraction and surrealism) and science (uncertainty, indeterminacy, probability), and then with the use of rational methods to develop nuclear weapons capable of destroying humanity.

Protest movements in the late 1960s made it clear that many social and political issues – civil rights, economic inequality, gender and sexual discrimination – are not susceptible to rational solutions and that what is considered true and just depends, at least in part, on race, gender, wealth and poverty. What seems to have happened is that the one approach fits all assumptions of rationality had lost their authority. In 2001 Stephen Toulmin (p.3) looked back over the previous thirty or so years and noted the remarkable loss of confidence in traditional ideas about rationality. In a sequence of books on pragmatism and social hope written in the 70s and 80s, Richard Rorty argued that truth is made, it is what we choose to believe in rather than something found in nature or identified empirically, and what some consider just and valid can be regarded by others with a different perspective as unjust and invalid. These differences cannot be resolved or adjudicated objectively. Even before that, in 1970, the French philosopher Michel Foucault (1970, p xvii) had described the outcome of the sorts of postmodern epistemological changes underway as ‘heterotopia’, a situation in which “things are ‘placed’ or arranged in ways so different from one another that it is impossible to find a common place beneath them”, a world in which somehow almost everything seems to be out of place.

” Heterotopia – a situation in in which things are placed or arranged in ways so different from one another that it is impossible to find a common place beneath them.” Michel Foucault 1970

From the perspective of place the rationalist ways of modernity had led to the placeless uniformity of international styles of architecture and planning of the 1950s and 60s. By 1990 modernity had given way to postmodernity and this was evident in the revival of place distinctiveness associated with heritage preservation, new urbanism, mongrel cities and hybrid places. Philosophers have had a rather different take on what has happened, though their suggestions also seem to come back to place. In the absence of generally accepted rational strategies Foucault proposed ‘local discourses’ that could make some sense of matters and suggest improvements to problems in specific contexts. Stephen Toulmin (2001, p. 7, p. 213) thought that the idea of reasonableness rather than reason or rationality allows us to steer a middle way and keep an even keel because this involves getting back in touch with the experience of everyday life and a return to “the world of where and when.”

This may seem very positive in terms of places, yet Foucault, Rorty and Toulmin realised that a loss of confidence in the authority of rationality, objectivity and empirical knowledge poses problems because it means that what is considered just, true and real becomes mostly a matter of who exercises the greatest powers of persuasion. The implication is that proposals to solve social and political problems will inevitably be contested by those who view them from a different perspective, and indeed that the very fact that they are problems can be questioned regardless of empirical evidence. Since 1990 this has been most obvious with denials that the climate is warming because of human activity and more generally in partisan politics and the echo chambers of social media where alternative accounts what constitutes the true history and identity of places are constructed on the basis of nothing more than shared and often exclusionary convictions. In other words, while postmodernity suggests that a fundamental shift in worldview might be underway, the consequences of this for places are enigmatic because they seem simultaneously to involve both enhanced distinctiveness and arbitrary parochialisms.

……………………..

Environmental and heritage protection, economic globalization, mobility, migration and hybridity, and new urbanism have all continued to expand and intensify. Their impacts on places have been complicated and compounded by trends since 1990 – including the world wide web, social media, climate change, place branding, placemaking, the international diffusion of localism, and now the coronavirus pandemic. These impacts will the subject of my next post.

References

Rachel Carson, 1962 Silent Spring

Michel Foucault, 1970, The Order of Things, Tavistock Press

Richard Rorty, 1982, The Consequences of Pragmatism, University of Minnesota Press

Richard Rorty, 1999, Philosophy and Social Hope, Penguin Books

Leonie Saundercock, 2003 Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cities of the 21st Century, Continuum

Deyan Sudjic, 1992, The 100 Mile City, Andre Deutsch

Stephen Toulmin, 2001, Return to Reason, Cambridge University Press