In a previous post I provided a synopsis of what I think are the four most important interacting trends that will affect the future of places – the place legacy, demographic changes, urbanization and climate change. To keep my discussion concise I abbreviated some data that supports my argument and did not refer to all the sources I had used. This (and two other posts, on place legacy and population, and on climate change and worldviews) are really long footnotes or appendices to that previous post which provide background material, data, and details about sources I used.

Urban Places and Urbanization

My main source of information on urbanization is UN World Urbanization Prospects [>data in Excel Files>Urban and Rural Populations>File 3, and >Urban Agglomerations>various files]. I have supplemented this with the illustrations and interpretations at Our World in Data Urbanization (based mostly on UN information).

| 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | |

| World Urban Population in millions | 751 | 1024 | 1354 | 1754 | 2290 | 2868 | 3595 | 4379 | 5167 | 5938 | 6680 |

| % Urban | 29.6% | 33.8% | 36.6% | 39.3% | 43.0% | 46.7% | 51.7% | 56.2% | 60.4% | 64.5% | 68.4% |

| More Dev in millions | 446 | 560 | 674 | 762 | 830 | 884 | 954 | 1004 | 1050 | 1090 | 1124 |

| % Urban | 54.8% | 61.1% | 66.8% | 70.3% | 72.4% | 74.2% | 77.2% | 79.1% | 81.4% | 84.0% | 86.6% |

| Less Dev in millions | 305 | 464 | 680 | 992 | 1460 | 1984 | 2641 | 3375 | 4118 | 4848 | 5556 |

| % Urban | 18.1% | 21.5% | 25.3% | 29.4% | 34.9% | 40.1% | 46.1% | 51.7% | 56.7% | 61.3% | 65.6% |

Although there is limited consistency in definitions between countries of what constitutes “urban,” (municipalities? metropolitan regions? built-up agglomerations?), so precise numbers are open to question, the trend towards increasingly urban populations and places is unarguable. The present is and the future will be overwhelmingly in towns and increasingly large cities.

The pattern of growth of urban populations in developed countries varies. Japan’s urban growth surged in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, but dropped to zero in the 2010s, and is expected to decline by 5 to 6 million a decade to 2050. In Germany and Spain urban populations grew rapidly in 50s and 60s but since then have stabilized at 1 to 2 million a decade. Growth of urban population in the U.S. has ranged from 15 million in the 1970s to 33 million in 1990s, and is expected to continue at about 25 million a decade to 2050. (Note that The Lancet population projections suggest faster declines and slower growth).

The 2020 Data Booklet on the Global State of the Metropolis by UN Habitat notes that what is significant about recent urban growth everywhere is that it has been increasingly concentrated in very large cities, urban agglomerations, metropolitan regions that have multiple centres (often an old core surrounded by several peripheral newer ones). This is expected to continue. Even in countries where overall population decline is projected, such as Japan and Spain, the largest cities are expected to at least maintain current populations. In 2020 the UN indicates there are 1934 towns and cities with more than 300,000 people (now referred to by the UN as “metropolises”), with about 60 per cent of the world’s urban population. Projections indicate that there will 429 additional metropolises by 2035 (or, as a recent Data Booklet by UN Habitat puts it dramatically, one every two weeks for 15 years). Almost all of these will, of course, be in Asia and Africa. By 2035 about 39 percent of the world’s population (3.47 billion) are projected to be living in metropolises with 300,000 or more people; cities of less than that will have about a quarter of the global population.

| Population | >10.0m | 5.0 to 10.0m | 1.0m to 5.0m | 500,000 to 1.0m | 300,000 to 500,000 |

| 1950 | 2 | 5 | 69 | 101 | 129 |

| 1960 | 3 | 9 | 93 | 132 | 164 |

| 1970 | 3 | 15 | 127 | 190 | 225 |

| 1980 | 5 | 19 | 174 | 247 | 297 |

| 1990 | 10 | 21 | 243 | 301 | 416 |

| 2000 | 16 | 30 | 325 | 396 | 456 |

| 2010 | 25 | 39 | 380 | 439 | 494 |

| 2020 | 34 | 51 | 494 | 626 | 729 |

| 2030 | 43 | 66 | 597 | 710 | 827 |

| 2035 | 48 | 73 | 639 | 757 | 846 |

| CITY | 2020 Population | 2030 Population | Growth 2020-2030 |

| Delhi | 30.3 m | 39 m | 8.7 million |

| Mumbai | 19.3 m | 24.5 m | 5.2 million |

| Shanghai | 27.0 m | 32.0 m | 5.0 million |

| Dhaka | 21.0 m | 28.0 m | 9.0 million |

| Kinshasa | 14.3 m | 22.0 m | 7.7 million |

| Lagos | 14.4 m | 20.6 m | 6.2 million |

| Kampala | 3.3 m | 5.5 m | 2.2 million |

| Dar es Salaam | 6.7 m | 10.8 m | 4.1 million |

| London | 9.3 m | 10.2 m | 0.9 million |

| Melbourne | 4.9 m | 5.7 m | 0.8 million |

| Toronto | 6.2 m | 6.8 m | 0.6 million |

| Atlanta | 5.8 m | 6.6 m | 0.8 million |

| New York | 18.8 m | 19.9 m | 1.1million |

| Paris | 11.0 m | 11.7 m | 0.7 million |

The UN Habitat Data Booklet indicates that between 1990 and 2015 urban land expansion rates were about double urban population growth rates. In other words, as populations were increasing densities were declining as metropolises spread outwards in relatively low density suburban, exurban and peri-urban settlements. This phenomenon is also apparent in the animations at the Atlas of Urban Expansion.

On New Cities in Africa and Asia:

Information about these is scattered. The ones in China are too numerous to mention here; there are also dozens in India, and many in other Asian countries and in Africa. Here’s a list in no particular order

Konza Technopolis, Nairobi

Gujarat International Finance Tech City (GIFT)

New Town, Kolkata

Gurgaon, New Delhi

King Abdullah Economic City, Saudi Arabia

Diomniadio, Senegal

Colombo Port City, Sri Lanka

Forest City, Malaysia.

Appolonia, Ghana

Hope City, Gracefield Island, near Lagos, Nigeria

Nova Cidade de Kilamba, Angola

Vision City, Kigali, Rwanda.

Putrajaya, Malaysia

Rawabi, West Bank Palestine

Duqum, Oman

Nurkent, Kazakhstan

Songdo, South Korea

Two general articles about the sameness or placeless character of these new cities are in Far and Wide, and The Guardian 2016:

For commentaries about new cities in India see this and this. The Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Development Corridor includes 8 new cities in Phase 1 and eventually perhaps more than 20. There is a YouTube video on India’s 20 New Cities here.

On African new cities see “Which way for livable and productive cities in sub-Saharan Africa” from the World Bank; Africa’s New Billion Dollar Cities; Non-Places; and Jane Lumumba “Why Africa should be wary of its new cities”. who offers cautions from the perspective of a planner and cautions: “What is worrying is that there is little recognition of place, economy, context and even poverty in these cities”.

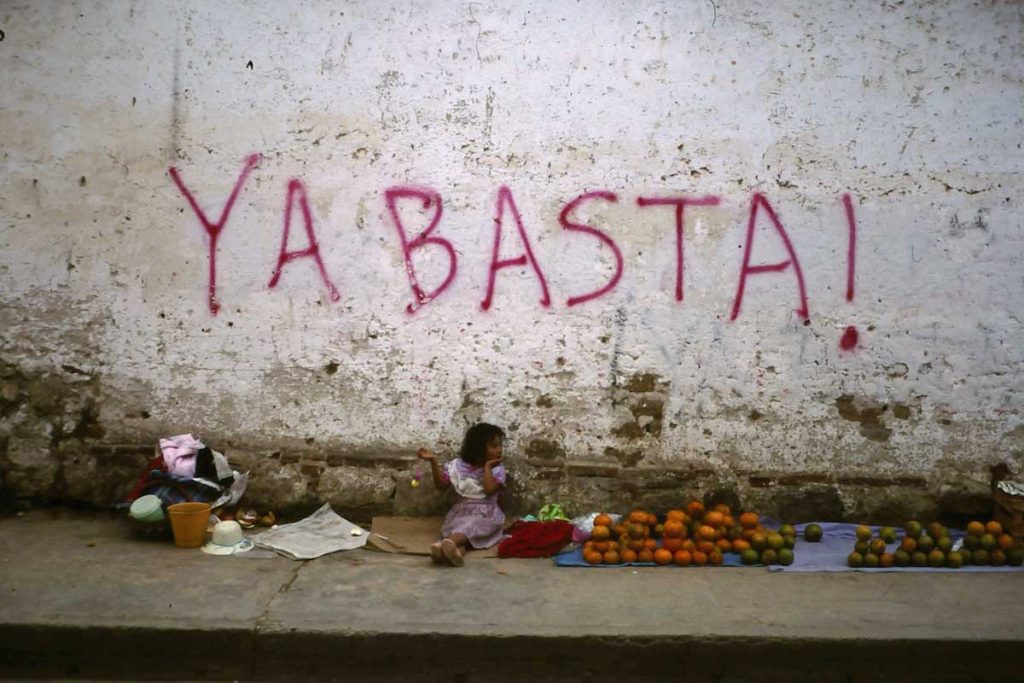

On Slums, Informal settlements and Poverty:

An academic overview and consideration of differences between formal and informal (slum) urban areas in Africa, how African urban dwellers actively enliven and shape their cities, is available here, (especially from paragraph 13 on, and the discussion about the lack of a clear line between formal and informal settlement). The growth of slums is described by UN Habitat in its Slum Almanac 2015, and in OurWorldinData-Urbanization see Urban Slum Populations.

In spite of huge strides since 1990 that have reduced the world’s proportion of people living in slums from 46 percent to 30 percent, the actual number of people in slums has not kept pace with population growth and has increased and perhaps stabilized at about 900,000 (Slum Almanac 2015, page 84). The Slum Almanac has concise case studies of 28 countries; in the Democratic Republic of the Congo 75 percent (22 million people), and in Nigeria 50 percent (42 million) and a decline from 75 percent in 1990 live in slums; in India the proportion is estimated to be 17 percent (about 100 million) and a decline from 55 percent in 1990.

The World Bank Strategy for Fragility, Conflict and Violence 2020-2025 estimates that by 2030 two thirds of the world’s extreme poor will live in cities threatened by fragility, conflict and violence. Violent conflicts have increased to the highest level in three decades; there are also the largest forced displacement ever, rising inequality and lack of opportunity, climate change, and violent extremism that are often interconnected.

The implication is that the places of the hundreds of millions of people living in deep poverty will be increasingly challenged by deteriorating environmental and political circumstances. They will be little more than temporary refuges, somewhere to hope and struggle for survival.

On Cities with Slow Growth and Incremental Change

My comments on places of slow growth are based mostly on my own observations of cities in More Developed Regions and how they have changed over the last fifty years.

Here some interesting details:

Densification: The City of Toronto is landlocked by other municipalities, so can only grow through densification. In terms of coverage it was almost fully built over by about 1990, when the population was 2.3 million. But by 2018 the population had grown to an estimated 2.9 million, mostly because of the construction of high rise condominiums in the core (where there are some 90 story condominium towers) and along arterial roads. A projection by the Province of Ontario suggests that the population will be 4.3 million by 2046. I lived in Toronto for several decades and have no idea how this increase can be accommodated.

The urban agglomeration of the Toronto region, which is enclosed by a Greenbelt, is projected to increase from 6.5 million n 2108 to 10.2 million in 2046.

In neither case are there indications of substantial changes in placemaking practices and how this additional growth is to be accommodated. Presumably more of the same, squeezed together and pushed up.

Flow through: Many world cities are destinations for international immigrants, many of whom then move elsewhere. In London natural increase contributes about 73,000 annually, domestic out-migration is means of loss of about 81,000, but international in-migration is about 79,000. So annual population growth is about 70,000. The population of London in 2020 is 8.9 m, and expected to rise to 10.4m in 2041.

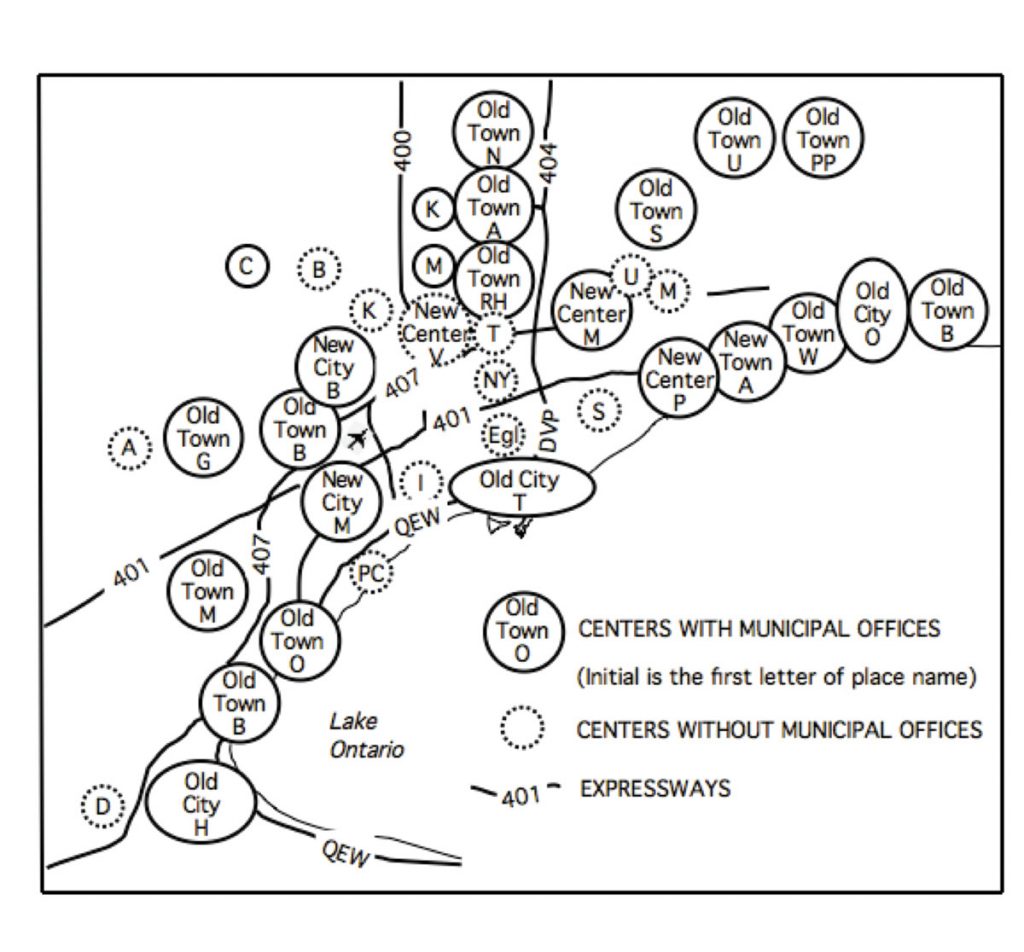

Redistribution There has been speculation in the context of Covid-19 that there will be flight to the suburbs away from high density central parts of cities. Whether this is the case or not, the evidence of urban land expansion at faster rates than urban population growth noted above suggests that central city densification will be matched by suburban expansion. There is some indication more compact and higher density suburban residential developments. The development of peripheral city centres in suburban municipalities may be ways to achieve some mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions by reducing commuting to central areas. This certainly appears to be the case in the Toronto region, which is developing as a polycentric metropolis.

The range of challenges of urban planning for a slow growing but changing cities: The Chicago Plan is a helpful model. It acknowledges the need to respond to decreasing federal state and local revenues, decaying infrastructure, climate change, and aging and diversifying populations

On Immigration and Hybrid Places:

A report by the US Census Bureau in February 2020 provides population projections under alternative immigration scenarios – zero, high, and low, as a supplement to standard projections that assume a continuation of present policies and trends. The standard projection (main series) is for a total population of 404 million in 2060. With high immigration the population is projected to reach 447 million by 2060, an increase of 124 million; in the low scenario it would reach 376 million. But with zero migration population will peak in 2035 at 333 million and decline to 320 million by 2060. In all scenarios the non-Hispanic white population will decline, but in the zero immigration strategy it would decline most – by 35 million.

(For comparison: the UN medium variant population projection for the US in 2060 is 395 million, and for zero immigration it is 333 million).

The implication is clear. If the population in the US is to grow it has to become more racially diverse. This is, in fact, the case in all countries in Europe, North America and Australia and New Zealand. And because immigration is concentrated in cities, the places and communities in those cities will become increasingly hybrid.

On Shrinking Cities:

There is a Shrinking Cities Research Network that has been mostly concerned with rustbelt cities in Germany and North America. As a specific case Detroit has coped with shrinking population for several decades and has a Demolition Department that has demolished 20,000 houses since 2014, and boarded up 21,000 more – a process that helps to protect and even enable the renovation of remaining dwellings.

Additional discussions of shrinking cities are at available here and there is an interesting examination by Francisco Sergio Campos-Sanchez et al, 2019, “Sustainable Environmental Strategies for Shrinking Cities based on successful case studies” in the International Journal of Environment and Public Health.

I am, however, aware of no discussions of the problems that will be presented by overall population decline in the second half of this century for urban and regional planning, and what this will mean for places and communities. The population forecasts published in July 2020 in The Lancet, discussed above, consider the health, social and possibly beneficial environmental consequences of sharp population declines that they identify as having already begun in 23 developed countries, and of peak population globally in 2064.

But there is no consideration in the Lancet article or, to my knowledge anywhere else, of what a 50 percent reduction in population will mean for the places where people live and no likelihood of future growth. From the perspective of place this amounts to something like a slow progression into a post-apocalyptic future of abandoned buildings and neighbourhoods being gradually overwhelmed by decay and invasive vegetation. At the very least it requires planning for the sorts of problems currently faced by Detroit – strategies for the ad hoc demolition of abandoned houses and apartment buildings. Should remaining inhabitants be clustered in compact settlements? How can that be accomplished? Or should some sort of very low density, dispersed pattern of places be permitted? But in this case, how can infrastructure of sewers, water supply and transit be maintained? What will happen to networks of expressways and hundred story skyscrapers that are no longer needed? Will places crumble like Rome in fifth century CE or be overtaken by vegetation like Mayan cities? Or will some sort of new, sustainable approach to places emerge?