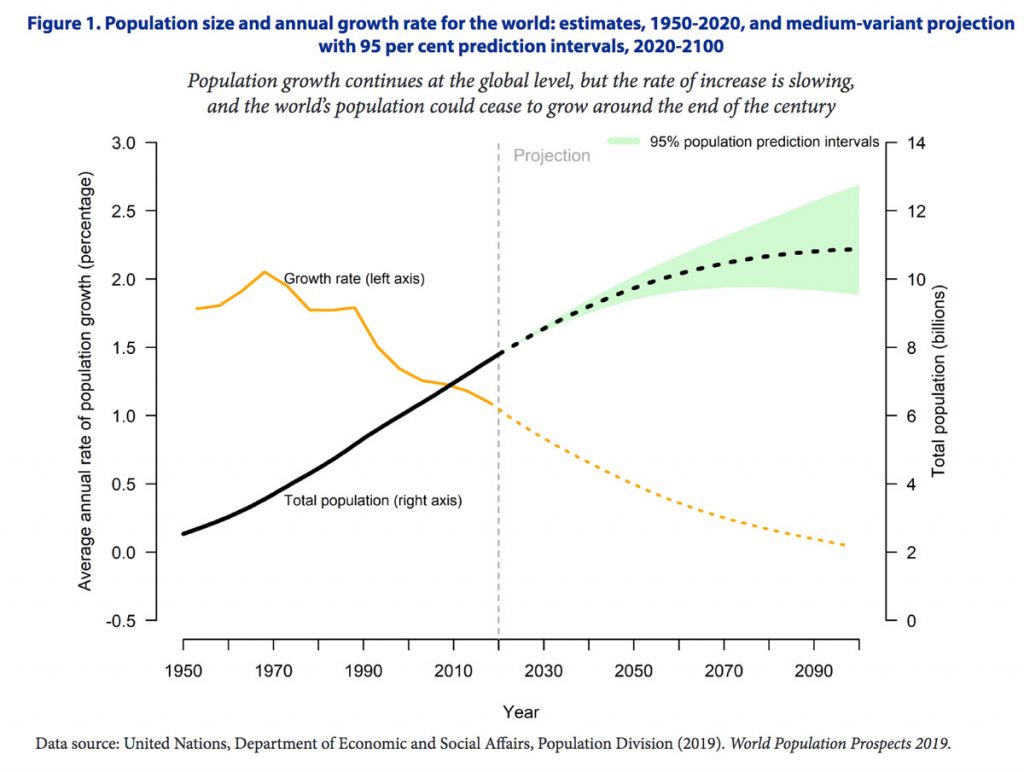

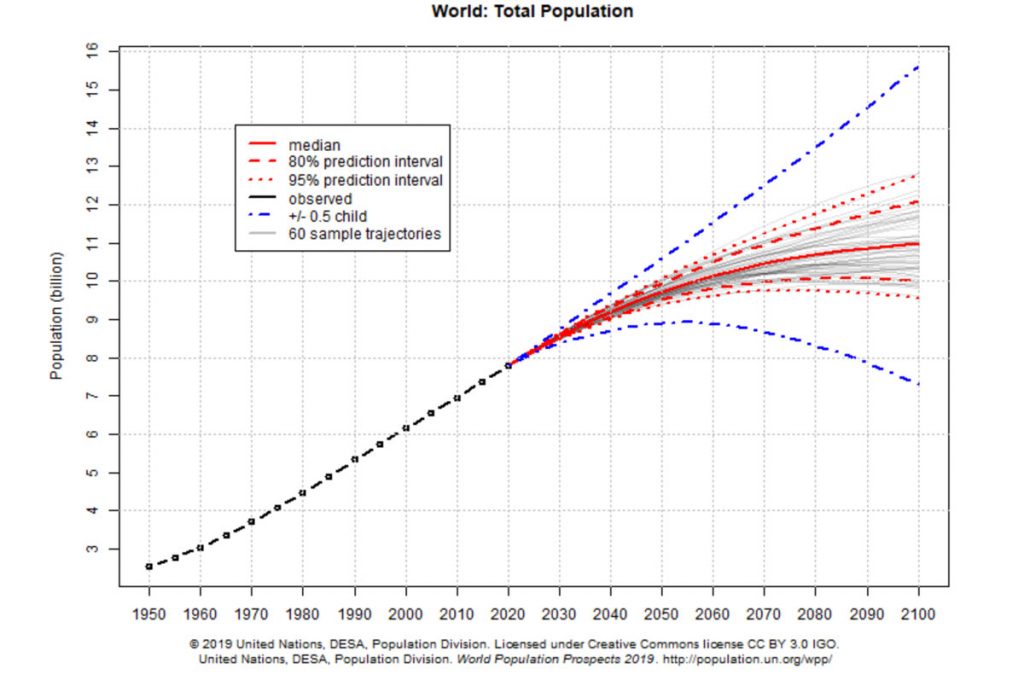

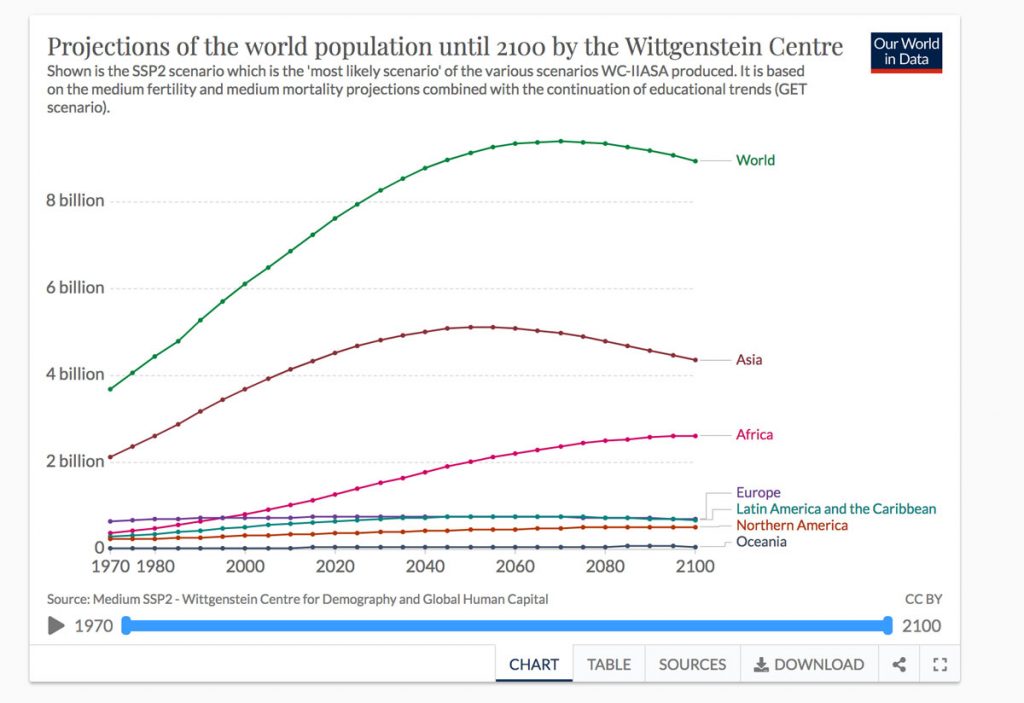

In a previous post I provided a synopsis of what I think are the four most important interacting trends that will affect the future of places – the place legacy, demographic changes, urbanization and climate change. To keep my discussion concise I abbreviated some data that supports my argument and did not refer to all the sources I had used. This (and two other posts, on place legacy and population, and on urbanization) are really long footnotes or appendices to that previous post which provide background material, data, and details about sources I used.

This post considers climate change (an issue on which there is a constant flow of material updating models and projections), shifts in world views that could have implications for places, and offers some concluding comments about the future of places.

Climate Change

Much of my interpretation of the impacts of climate change on places is based on the 2018 IPCC Special Report on the impact of 1.5C global mean temperature increase and the importance of taking significant actions before 2030. This report indicates what is required to meet the 2016 Paris Accord on climate change to keep the warming below 2C.

All IPCC reports are challenging, partly because the scientific models are complex, and partly because they have, in effect, been written by committees and have to be approved by almost two hundred participating nations. This particular report is a sort of literature review, the diagrams are complicated and much of the information is so carefully qualified it is difficult to grasp.

The clearest statement on the implications of global warming I have identified is Cross Chapter Box 8, Table 2, in Chapter 3, Impacts of 1.5C warming on Natural and Human Systems, near the end of section 3.7 Knowledge Gaps. This offers three scenarios of possible futures, one in which there is immediate strong international support for achieving net zero emissions; a second in which actions are delayed beyond 2030 but implemented after the effects of climate change become apparent; a third in which actions are uncoordinated and not taken until late in the century and the global temperature increases to 3C above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

In the latter two cases the consequences will be considerable. A 3C rise, the report suggests, will mean that from the perspective of 2100 the world as it was in 2020 is no longer recognizable. Migration and forced displacement will be extensive in some countries, the well-being of people will generally have decreased, and levels of poverty increased. See also this discussion at new cities about climate migration.

This Special Report was written in the context of a well-argued assumption that a doubling of atmospheric C02 will lead to a global mean temperature increase of between 1.5C and 4.5C. Recent research re-examining this assumption has concluded that the range of probable warming will be narrower than this, probably somewhere between a minimum of 2.6C (which is higher than the preferred Paris Accord value) and maximum of 3.9C. Less than was feared, but more than was hoped. With a global mean temperature increase of 2.6C there will still be an array of serious impacts and emissions need to be sharply curtailed to prevent anything more than that.

The IPCC Special Report is clear that: “There is no single 1.5 C warmer world.” This is because the effects will differ from region to region. In addition, there are varying degrees of uncertainty about the consequences of climate change, partly because they are so complex, partly because they interact with other environmental, social and economic processes, and partly because the effects of actions taken to mitigate them could be delayed. There are also possibilities of overshoot and tipping points that lead to a cascade of consequences that cannot be reversed. To acknowledge these uncertainties the report is filled with terms such as Likely, Very Likely, High Confidence, Medium Agreement etc. Nevertheless, the overall and clear conclusion is that the effects of climate change are going to be severe unless substantial mitigation measures are implemented very soon.

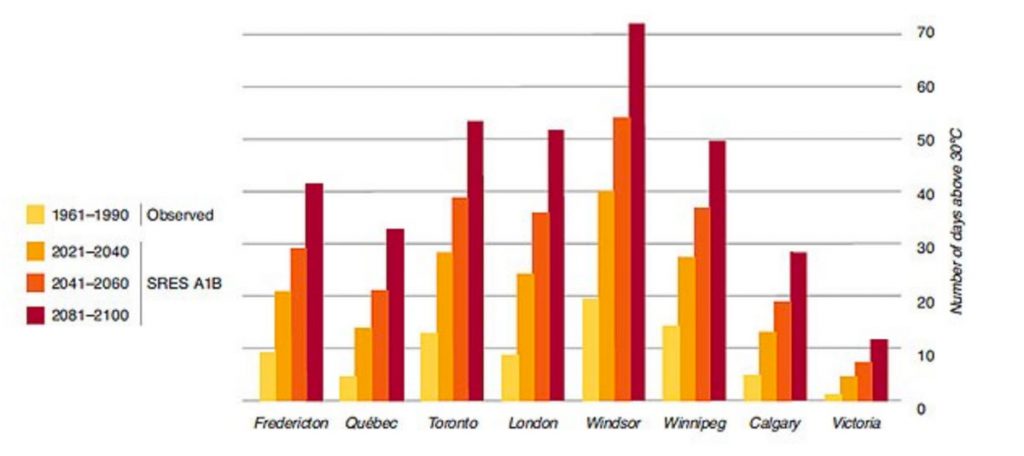

These effects can seem obscure when they are stated in general terms about degrees of warming or migrations. A straightforward indication of their impact on specific cities in Canada is indicated in a forecast of the increase of the number of very hot days (exceeding 30C). Several cities will go from under two weeks of very hot weather to about two months, which greatly increases heat related health problems. See also this interactive website about weather condition in cities in 2100.

A particularly pessimistic indication the future effects of climate warming is suggested by research about increases in heat and humidity that will result in conditions too severe for human tolerance. This has suggested that there is evidence that wet bulb temperatures exceeding 35C (the upper physiological limit for prolonged exposure), which climate models projected to happen initially in mid-century, have already been reached or approached in localized cases in South Asia, coastal Middle East and coastal south east North America.

A recent article in the New York Times by Abrahm Lustgarten suggests that currently about 1 percent of the world experiences temperatures that make it barely livable, and if current trends continue by about 2070 as much as 19 percent could become an unlivable hot zone spreading across Africa from Nigeria to Ethopia, plus most of India and Pakistan, large parts of Indonesia, an a section of northern Australia. I can’t find another source for this particular projection but if it is accurate many of the places in these regions will have to be abandoned. Even if things turn out to be less severe, there is still a very strong possibility that climate warming and sea level rises will lead to mass migration. The article provides strong evidence that crop failures caused by climate change in Central America have already led to migrations, and that sea level rises and increasing salination could cause severe problems in the Mekong Delta, the Nile Delta and Iraq. Some recent research suggests 300 million people could experience annual flooding by 2050 if there are no significant reductions in C02 emissions, many of them in China and Indonesia, but Miami, New Orleans, New York, Boston and San Francisco are probably among the top ten cities that will be most impacted.

On the other hand a recent report about successful adaptations to climate change in the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 offers a promising instance of how successful warning systems and evacuation procedures can be. A typhoon during the pandemic caused very little loss of life because effective procedures are now in place. Even so, the monsoons in 2020, perhaps the heaviest in a decade, have resulted in one third of the country being underwater and have displaced 1.5m people.

From a different perspective a recent article in The Atlantic makes that important point that it will be necessary to transition several countries, including Nigeria, Algeria, Libya, Mexico and Iraq, from economies dependent on oil to economies that are climate friendly and this will not be easy. In Nigeria half government revenue is dependent on oil; recent price declines already mean a substantial loss of income in a country where 80 million people live on less than $1 a day. The consequences of failing to manage a smooth transition will increase the fragility associated with weakened governments, economic depression, international migration, severe violence and terrorism.

Changing Worldviews

In a previous blog I discussed the way that rationalism has lost its once privileged position. Some philosophical sources for this are the various writings of Richard Rorty, Michel Foucault, and Stephen Toulmin. Not every philosopher agrees of course, but it has become very difficult to maintain that an objective, materialist view of the world is the only valid or most correct one.

As rationalism loses its privileged position other perspectives are emerging, including, for example, those that emphasize gender and racial inclusion. From the perspective of place I think the following are particularly important.

Ecology and Environment. I am not aware of anyone else who has made my argument that the idea of working with natural processes rather than subjecting them to human domination is an innovation of the last 150 years, initially manifest in the creation of national parks (and at about the same time coining the word ‘ecology;), followed by the conservation movement, environmentalism, ecological planning, and most recently sustainability. It seems clear that this ecological view has become increasingly widely accepted and is certainly in the background of the Green New Deal. It can only become stronger as the impacts of climate change become more apparent.

Electronic Communications: Marshall McLuhan’s argument that the medium is the message means that the prevailing medium of communication has a powerful affect on enduring social practices and values. In other words, how things are communicated is, in terms of social processes, more important that what is communicated. As one example, the linearity and straightforward clarity of printing provided a mostly visual medium that has made possible scientific rationalism and linear, orderly thinking. In contrast, electronic media have characteristics of oral media that promote more emotional forms of communication with an emphasis on feelings and opinions rather than objective evidence. Although electronic communication began with the telegraph in the 1840s, it has only since 1990 and the invention of the world wide web that it has acquired a popular and almost omnipresent presence. In less than 30 years it has been adopted by most people in the world (over 50 percent use the internet in some way) and its impacts on social life and politics have been extensive and intensive.

Place-based localism is a relatively recent phenomenon, especially in the current form that involves electronic links between specific places, though its roots as an explicit idea go back to the 19th century. See my post discussing electronic media and place here.

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz in Local Knowledge (Basic Books 1983, p.16), wrote that:: “To see ourselves as others see us can be eye-opening. …. But it is from the far more difficult achievement of seeing ourselves amongst others as an example of the forms human life has locally taken, a case among cases, a world among worlds, that the largeness of mind without which objectivity is self-congratulation and tolerance a sham, comes.”

The importance of localism in a global context has been recognized by UNESCO, while the 2018 IPCC Special Report refers frequently to the importance of local mitigation and adaptation in concert with international, national and regional actions, including the possible need for lifestyle changes and shifts in urban planning (see especially SR 1.5C Chapter 4). The Atlantic has had a series of articles about the achievements of local initiatives in the United States, in some cases in spite of federal and state indifference (for instance here).

While a turn to localism has many potential benefits for places, including improved sustainability, independence and self-sufficiency, and shorter supply chains, it does require cooperation between different levels of government if it is not to deteriorate into exclusionary attitudes and survivalist communities. My main point is that, for good or bad, there seems to be a shift towards thinking about the world in terms of localities and places. This is an important rebalance from what has all too often been centralized policies and standardized practices that pay scant attention to whatever is local. Localism now means understanding how places are interconnected electronically and through travel, and recognizes places in their regional, national and international geographical contexts.

Overview

My point in this series of posts about the history and future of places, and indeed this entire website, is that place is not some sort of incidental amenity. Its value spans generations and cultures, and is manifest in attachment, belonging and dwelling somewhere, in acknowledging genii loci – the spirits of places – through the creation of sacred or protected sites, in putting down roots, and in a commitment to home and efforts to defend it and to rebuild after disasters. Although this value is not universally shared (some pay little attention to place because their interests are focused on economic gain or other matters), evidence from archeological sites and historical records shows that places always seem to have been important aspects of how people everywhere have experienced and modified the world.

The conclusion I take from this is that people will find a way to make places that are relatively distinctive and meaningful regardless of the circumstances, no matter how bleak or difficult. Some aspects of those places are personal – gardens, decorations, memories. But their larger forms and appearances in villages, towns, neighbourhoods and cities are determined by prevailing social and cultural beliefs, circumstances and practices. While these constantly change in small ways, from time to time they have undergone substantial changes as populations have grown, civilizations have expanded or shrunk, technological innovations have happened, and new ideas about what is valuable and beautiful have emerged. Each era has left a place legacy that is a record of its more or less distinctive practices of placemaking, a record that is biased towards wealth and power because those are vested in structures such as pyramids, temples, castles, and palaces that were usually built to last.

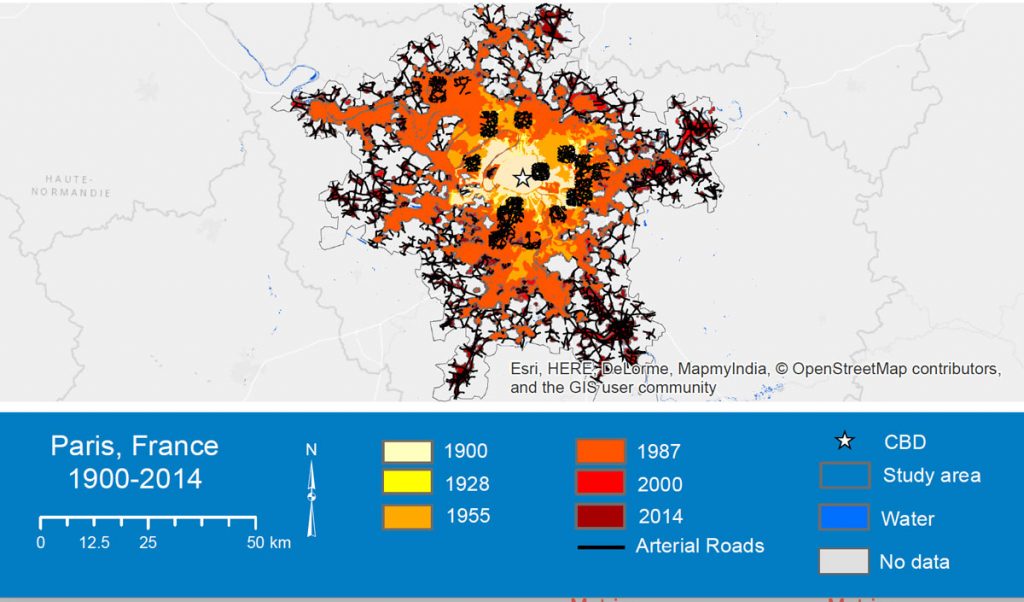

Given this historical record, it is to be expected that the future of places will consist in part of a legacy of existing places, and in part of placemaking responses to changing social and environmental circumstances that, according to current projections, will include the considerable challenges of population decline, increasing urbanization, and the diverse impacts of climate warming, all of which are global in scope but local in both cause and impact.

At the present time it is far from clear how these challenges will be met and therefore what associated changes to the character of places where people live will be like. This is partly because so much attention is focused on short term concerns and the absence of any widely shared vision of the future. In the current moment this means coping with the covid-19 pandemic in the broader context of political partisanship, the apparent decline of democracy, geopolitical realignments, faltering globalization, the disruptive effects of social media and electronic communication, growing inequality, and in the background concerns about genetic engineering and artificial intelligence. These are problems that are actually or potentially interconnected in ways that are so complicated that they resist straightforward representation or understanding.

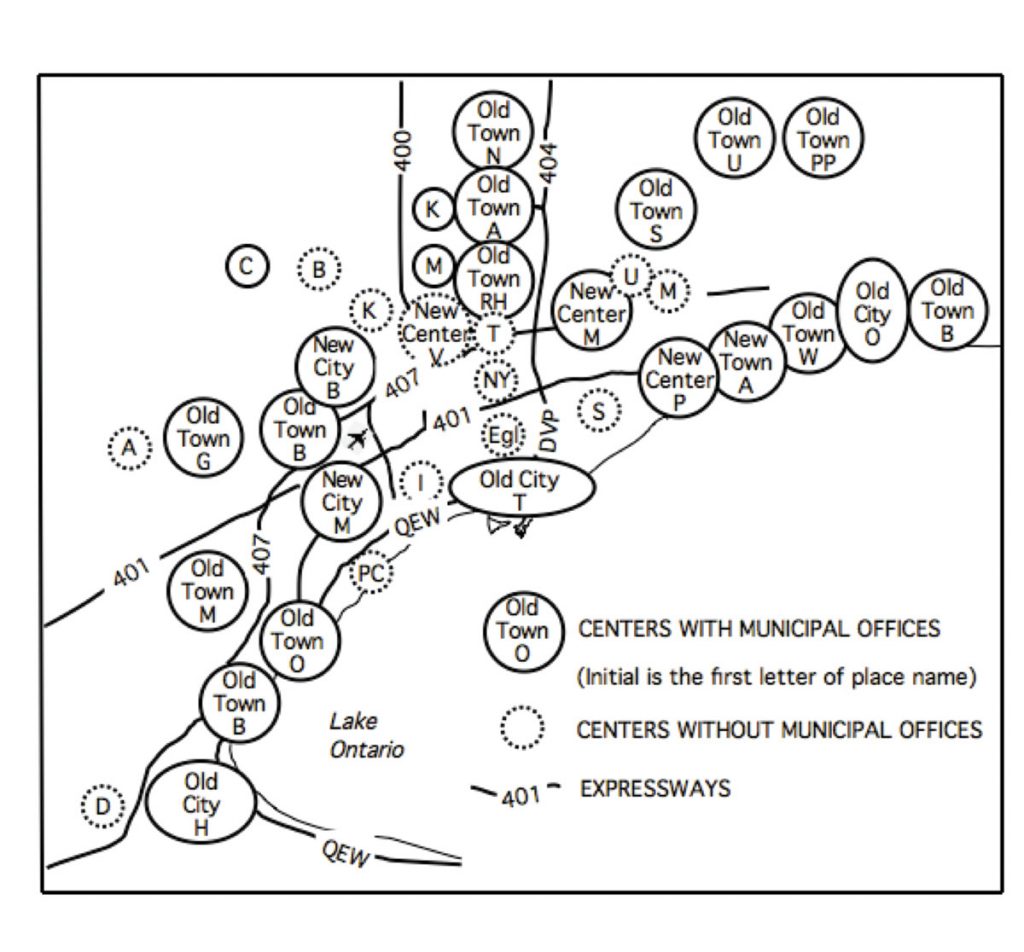

This complexity makes it impossible to predict what or indeed whether substantial changes to the character of places will happen in the course of this century. There is no obvious emerging worldview or philosophy, equivalent for instance to rationalism with its companion renaissance aesthetic and notions of progress in the seventeenth century, or industrialization in the early nineteenth century, that might provide hints about how urban neighbourhoods and places in 2050 or 2100 might differ in appearance and character and the patterns of everyday life from those of 2020. What can be said with a reasonable degree of confidence is that places will be mostly in very large cities, some of which in the developed regions of the world will already have declining populations and many of which in less developed areas will be slums of some sort. And unless very substantial actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are taken in the next few years, which seems increasingly unlikely, almost all of them will experience hotter and more extreme weather, in some cases so extreme that large sections of their populations will be forced to migrate to places in more moderate climates, where they are unlikely to be very welcome.

To put it succinctly, projections of population, urbanization and climate change, which are probably the most dependable projections available, suggest that the future of places in the twenty-first century, will for many people, be filled with increasing and unprecedented challenges for which past practices offer few solutions. There is currently little to suggest that new ways of making places will develop to address these challenges.