Perhaps the greatest omission in my writing about place is how it relates to health. My inclination has been to consider the emotional stress caused by uprooting, displacement and destruction of place as important mostly for the way it demonstrates the existential significance of belonging to a place. But there is substantial evidence, supported by a body of scientific literature, that many characteristics of places and local environments have an impact on the physiology of health.

The connections between health and place have been part of medical understanding since the origins of medicine, but there has been a flurry of academic research exploring these connections since about 1990. As I wrote this post I became increasingly aware that this aspect of place deserves far more consideration than a single post can provide. Indeed, I think a comprehensive account could take years. So this very short overview of the history of place in health, plus some links to recent researchand a few comments about how place seems to be understood in that research, is no more than a sort of outline introduction.

Historical Background

Connections between health and place have been acknowledged since the beginning of modern civilization, usually by linking the quality of health to the environmental conditions in specific locations. For example, the Ancient Greek philosopher Hippocrates, widely considered the father of medicine, began his book Airs,, Waters, Places, which was written about 400 BC, with the statement that anyone who wants to investigate medicine properly should first of all consider the seasons, winds and waters “such as are peculiar to each locality.” He elaborated these and then recommended that, “if one knows all of these things well, or at least the greater part of them, he cannot miss knowing, when he comes into a strange city, either the diseases peculiar to the place, or particular nature of common diseases…” [Section 6].

Hippocratic ideas that health was related to the environmental quality of a place endured through the centuries, and, for instance played a role in the Middle Ages when citizens protested against foul air and stench from slaughterhouses, and also in the belief that, for those with the means, it made good sense in times of epidemics to escape from cities to the countryside (see, for example, Carole Rawcliffe, 2021, “A Breath of Fresh Air: Approaches to Environmental Health in Late Medieval Urban Communities.” Palgrave Macmillan).

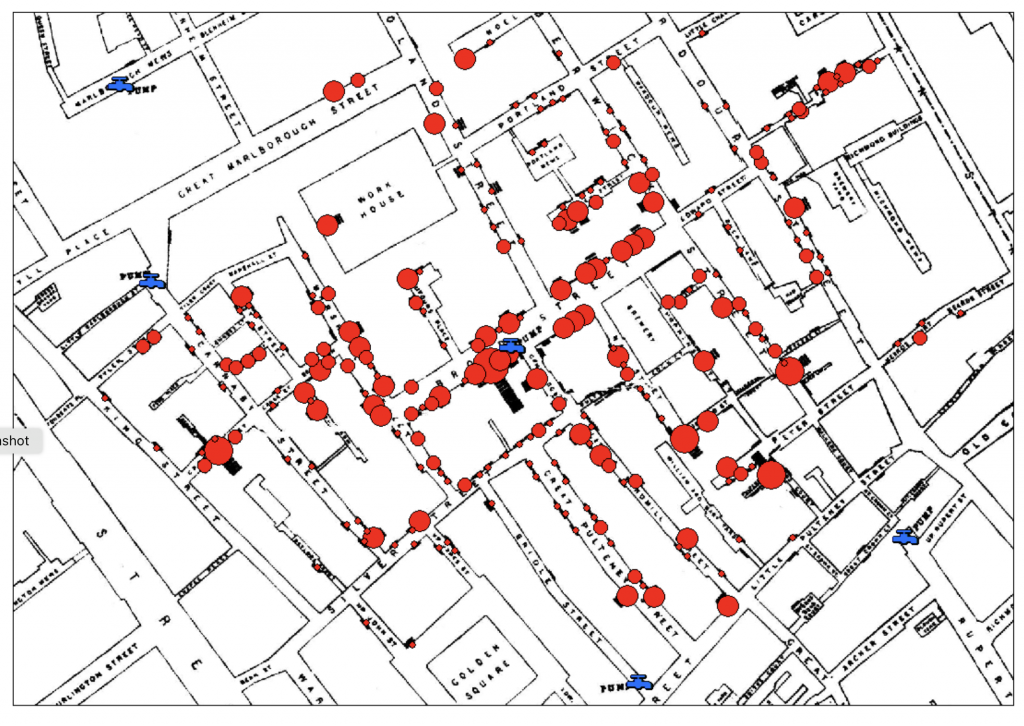

It was, however, not until the mid-nineteenth century that the actual causes of place-based disease and ill-health began to be identified. In this regard, John Snow’s epidemiological study in 1854 that linked cases of cholera to a specific water pump in London was especially significant. He demonstrated through careful investigation of the location of the cases of cholera and where the families had obtained water that it was not bad air that was responsible, but water contaminated with sewage. Causes of diseases are rarely quite this specific (though the search for a precise origin for COVID suggests it is an idea that is hard to shake). Nevertheless, the recognition that health conditions, whether in their manifestations or their causes, often have a geography that can be mapped and that this can help in their treatment continue to be very important.

The Journal Health and Place

Subsequent studies of the environmental determinants of health have mostly followed along the lines of Snow’s systematic, scientific investigation of manifestations and causes. With the rise of interest in place and sense of place in the late twentieth century these began to be framed specifically in term of place and health, culminating in 1995 in the creation of the academic journal Health and Place. Initially this was a modest publication – four issues a year with a handful of articles and research notes, but it got increasing international attention, has expanded to six issues a year, each one with more than twenty articles and numerous research notes, many of which address public health issues. At the top of every online issue of Health and Place is a statement that makes its aim explicit: “Designed to the study of all aspects of health and health care in which place or location matters.”

The first edition of Health and Place in 1995 had an editorial by Graeme Moon, “(Re)placing research on health and health care”, in which he stated the aim of the journal is to publish “research into health and health care which emphasises differences between places, the experience of health and care in specific places, the development of health care for places, and methods and theories underlying these in geography, sociology, public health, anthropology, and economics.” (Volume 1, No 1, 1995, pp.1-4).

Moon noted specifically that communicable diseases spread geographically, which is to say from place to place, and that chronic disease can vary geographically. Furthermore, health policies vary between nations and regions, and often have singular local impacts because access to health services are not the same everywhere. It is, he suggested, a trivial observation to say that conditions affecting health are different in different places: the key questions are why is this the case, what are the issues of location and mobilitiy, and in what ways do people in different places experience sickness and use health services differently?.

My impression, after a rather cursory investigation of the recent research published in Health and Place, is that these questions are ones that continue to be explored in the Journal, with an emphasis on public health, and now across a wide international range of case studies.

How Does Place Affect Health?

This question is addressed in a program of the Center for Disease Control of the United States.

The places of our lives, it suggests – our homes, workplaces, schools, parks, and houses of worship – affect the quality of our health and influence our experience with disease and well-being. And it uses a variety of geographical and GIS methods to explore how this might be the case, including a framework for the “geographical determinants of health”. The aims of the program are to define the geospatial drivers of health with an emphasis on factors that vary by place. Place is described simply as “… a broad and evolving concept… the places of our lives define, shape, and influence the health determinants we face throughout our lifetimes.”

The intention of this branch of the Center for Disease control is to promote research into the relationship between geographic variations of disease and environmental, demographic, behavioural, socioeconomic, genetic, and infectious risk factors. Examples of the fields of research include investigations of space and time trends in the spread of Ebola and Zika viruses, geographical variations in cancer incidence, and spatial components of the opioid crisis in the US, such as where overdose deaths and drug-seeking behaviours happen.

Epidemiology

Books and websites about epidemiology often note that three basic variables in the investigation of patterns of disease, are person, place and time (or Who, Where and When, as Wikipedia has it). Person here refers both to individuals and to social circumstances, and time acknowledges that diseases wax and wane over years, decades and ccenturies. Place, is not always defined, but one book notes that it can refer to more than one thing, for instance “a location, an area, a city, a state, or a country.” However, since place is primarily a spatial concept, it is now frequently described and understood in terms of the coordinates used in geospatial data and GIS, which means that place patterns are defined primarily by what the data indicate.

An important idea in epidemiology is that where somebody lives, works, and travels can provide clues about relevant exposures to particular diseases. Disease frequency can vary geographically between regions, or between neighbourhoods in cities, or between urban and rural areas, and clues to the reasons for this might be found in social conditions (relative wealth or poverty), proximity to polluting industries, or possibly aspects of the natural environment.

(Source: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/index.html)

The Definition of Place in Health and Place Research

My impression is that the notion of place in much research into health and place is taken to be straightforward and self-evident. A place consists of a any relatively distinctive, two dimensional spatial fragment of geography, whether a neighbourhood, a city, an ecosystem, a region, or a country. This “broad and evolving concept” as the Center for Disease Control describes it, allows “geospatial data”, in other words any information that has a geographical location, to be analysed using GIS methodologies as way to find statistical, spatial connections between diseases and environments.

Some Further Ideas about Place in Health Research

There is no question that this is an invaluable way to grasp the reasons why the qualities of health and disease vary from place to place. But place also an experiential phenomenon, something with depth, filled with meanings and associations, often an essential part of the very identity of individuals and communities. My impression is that these are peripheral to much of the research on place and health. However, they are not entirely ignored. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but the following are some instances of topics that, implicitly or explicitly, consider relationships between health and place as an experiential phenomenon. Of these, I think only Therapeutic Places have been studied with regard to the phenomenological importance of place.

• Healthy Cities

The initiative to consider cities from the perspective of health does not consider place explicitly, but the top page on the WHO website on healthy cities begins with this quote from the Ottawa Charter of 1986 about health promotion: “Health is created and lived by people within the settings of their everyday life; where they learn, work, play, and love.” In other words, the widely promoted idea of healthy cities is about the urban places where people live, and with which they are practically and emotionally engaged, and about finding ways to enhance that engagement.

• Pollution and Solastalgia

Environmental scientists in Australia have identified a connection between solastalgia – the deep emotional feeling of a loss of attachment to place without ever leaving it – and the effects of air pollution on deteriorating health (see my post on solastalgia). In other words, local pollution and forms of environmental damage that cause physiological health problems also undermine people’s attachment to place. (see Nick Higginbotham et al, 2010 “Environmental injustice and air pollution in coal affected communities, Hunter Valley, Australia,” Health and Place, March 2010, 16(2), pp. 259-266).

• Aging in place

A growing issue in much of the developed world as populations age is the tension between people’s wish to continue living in their homes and communities, in the places to which they belong, even as their needs for health care become more pronounced. See for example, this website of National Institute of Health

• The Experience of Quarantine

Quarantine is a disruption to the everyday experience of place. It can mean escaping to somewhere thought to be safe from an epidemic (Newton was quarantining from an outbreak of plague Cambridge at the family estate in Woolsthorpe when he saw the apple fall). It can mean being confined to a colony of individuals who have been excluded because share the same disease (historically, colonies of lepers, sanitoriums for tuberculosis patients). It can mean being confined to one’s own house until the epidemic has subsided, which happened in numerous cities during COVID-19, which caused serious psychological problems for some. This demonstrated that while home might be an intensely meaningful place, that relationship needs to be mitigated by the freedom to get away from it. Too much home is not a good thing. See, for example, this website on aging in place.

• Homelessness

The widespread epidemic of homelessness is, more or less by definition, the loss of attachment to place. It is also a circumstance that exposes individuals to disease, whether because of exposure to the weather, or because of exposure in crowded shelters, or because of inadequate access to sanitary facilities. This is explored, for example, in Lisa Vandemark 2007 “Promoting the Sense of Self, Place and Belonging in Displaced Persons: The Example of Homelessness” Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 21(5), pp. 241-248.

• Therapeutic places

Therapeutic places are those which are believed to have the power to heal. They includes places of pilgrimage, such as Lourdes in France, where miraculous cures are said to have occurred. They also include social and natural environments that appear to facilitate convalescence. This 2018 bibliographic survey on therapeutic landscapes and healthy places in Social Science and Medicine, lists many publications on the topic.

.