Common preamble to three posts on changes to place over the last 50 years

I recently posted an unpublished and not previously circulated essay at Academia.org on the ways that places and place experiences have altered since about 1970. It draws on some of my posts on this website, and also on my publications about place (mostly book chapters that might not be easily available) since about 1990. My main reason for writing the essay is that experiences of being rooted in place, belonging, attachment and so on, and indeed the forces of placelessness that might be eroding these, are not timeless and unchanging. What made sense in 1970, when I was writing my book Place and Placelessness, needs to be updated both because there are now practices for protecting, making and promoting places that did not exist then, and because the ways places are experienced have shifted dramatically in a world of cheap air travel and omnipresent electronic devices.

I assume that those looking at this website and those reading Academia are mostly from two different audiences, so this and two additional posts offer a sort of point form summary of my Academia essay, which is about 60 pages long. This post (#2) deals mostly with changes since 1970 to the ways places are experienced. A previous post (#1) considered recent changes to ways places are made. The third post (#3) offers some theoretical speculations about changing relationships between place and placelessness and what they portend for the future of places.

Although they are really only summaries of ideas, I hope that together the three posts offer enough suggestions about recent changes for you to be able to explore them further, perhaps question some conventional assumptions about roots and sense of place, or, conversely, to refine arguments that place provides continuity in the face of change.

A small installation I came upon in a coffee shop in British Columbia that expresses a complementary relationship between roots and mobility in experiences of place.

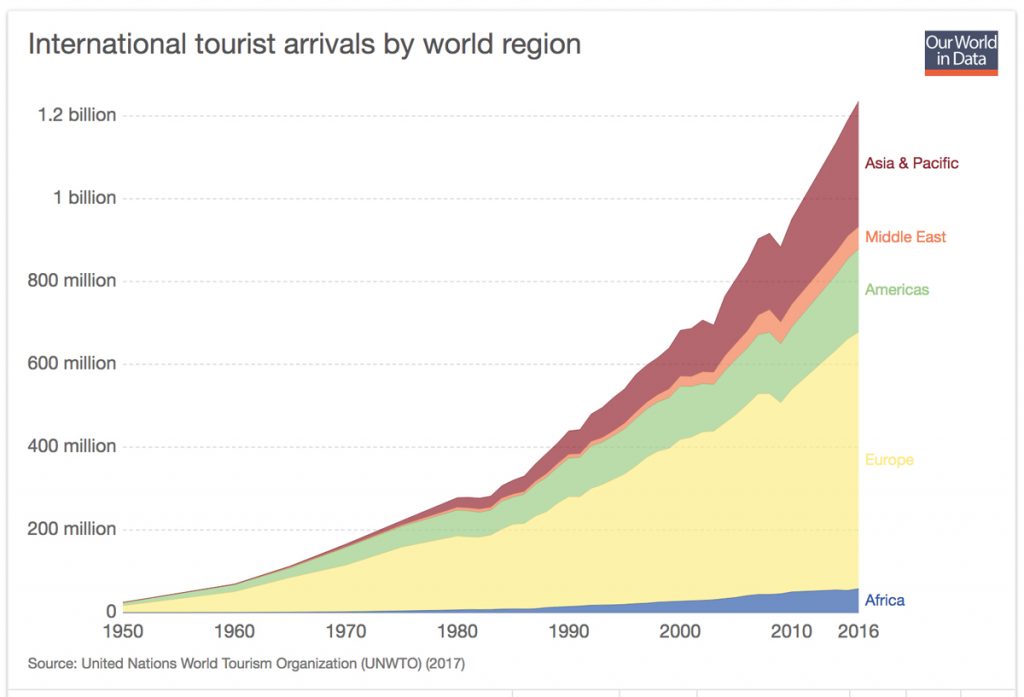

Increased Mobility In 1965 the Interstate highway system in the US was under construction but far from complete, and there were no motorways in Britain; both now have networks of expressways that have effectively shrunk the distances between places. In 1975, when the world’s population was about 4 billion, there were estimated to be about 250 million motor vehicles in the world, or one for every 16 people; in 2018 there are about 1.25 billion for 7.6 billion, or one for every six people. In 1950 there were about 22 million international tourist arrivals, which amounted to less than one per cent of the world’s population travelling internationally; by 1975 the number had grown to 222 million, equivalent to 6 per cent of the world’s population; in 2016 the there were over 1.25 billion such arrivals, equivalent to 17 percent of the global population. At any given moment there are now estimated to be about one million people in the air, on their way to visit and experience for themselves formerly exotic places, to see their families, or to work.

This graph showing the growth of tourism clear shows one aspect of the change in mobility that has happened over the last fifty years. Source: https://ourworldindata.org/tourism, and data from UN World Tourism Organization.

In short, fifty years ago most people experienced a few places quite slowly; now many people have easy, quick access to many places, and many of which are experienced quite briefly. The consequences of this increase in mobility for place experience means that the deep but confined sense of a few places that prevailed for most of human history, has in half a century for most people been replaced by a relatively shallow experience of many places. Whether this trade-off is beneficial is, I think, an open question.

Merits of Tourist experiences and the Inauthentic Authenticity of Mass Tourist Destinations In effect, what has happened is that travel and tourism have been democratized. No matter how brief, crowded or programmed the consequent experiences of place may be, experiences of many places involves opportunities for appreciation and learning. It is difficult to argue that this is not beneficial because it increases appreciation of the variety of the world and its people, and it challenges the parochialism and exclusion that can all too easily follow from a narrowly rooted sense of place.

On the other hand mass tourism is a mixed blessing for those places that are on its receiving end, where sheer numbers are beginning to undermine the very place qualities that made them attractive. Venice is perhaps the most extreme example, where the dwindling resident population of about 55,000 is confronted annually by about 25 million visitors, many from cruise ships, but Barcelona, hiking trails in New Zealand and many World Heritage sites, such as the Pantheon in Rome, shown here in 2017, are confronting the same problem of authentic place qualities being eroded by sheer numbers of visitors.

On the other hand mass tourism is a mixed blessing for those places that are on its receiving end, where sheer numbers are beginning to undermine the very place qualities that made them attractive. Venice is perhaps the most extreme example, where the dwindling resident population of about 55,000 is confronted annually by about 25 million visitors, many from cruise ships, but Barcelona, hiking trails in New Zealand and many World Heritage sites, such as the Pantheon in Rome, shown here in 2017, are confronting the same problem of authentic place qualities being eroded by sheer numbers of visitors.

Non-Place Places The term “non-places” was coined by the French anthropologist Marc Augé to refer to airports, service stations, hotels, theme parks, hospitals and similar facilities that have no history, no resident population, and where everyone is an outsider – a client, customer or employee. They have standardized elements that can be understood by outsiders and they have certainly made travel much easier.

Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam is a non-place with few signs in Dutch, but, as the indigenous art installations at Vancouver International indicate, even a non-place can be a distinctive place.

Paradoxically, as Tim Cresswell’s study of Schiphol has shown, they also have their own identities for those who use them frequently or work in them, and their designs and art installation often reflect the local setting. To that degree even non-places are places.

Multi-centred Lives Lucy Lippard describes modern society as multi-centred because many people live for extended periods in different places, or effectively have two different homes (where they come from, where they live now, a cabin or cottage they can escape to,and so on). Multi-centredness is not entirely new, but it has intensified over the last few decades. The UN reports that that are now over 250 million international migrants in the world, and one third of those have migrated since 1990. Global diasporas, transnationalism and multi-centred lives have become a major aspect of the demographic reality of the present age.

There can be little doubt that multi-centredness has changed how people experience and relate to place. For example, research by Stephanie Taylor in Britain has suggested that for women the ‘born and bred narrative’ of long-term family connections to a home place is questionable as increasing numbers choose to participate in the opportunities offered by mobility between places.

Evidence of hybridity in a mongrel. This poster was posted by the Toronto Transit Commission about 2010.

Mongrel Cities and Hybrid Places, yet the Beginnings hold Everything Diasporas are not a new phenomenon, but their variety and character has given rise to cultural heterogeneity in cities that represents a substantial change especially in Anglo-American and European cities that had previously homogeneous cultures. The result of immigration either from former colonies or from places with very different cultural histories has given rise to what have been called “mongrel cities”, filled with hybrid mixtures of races, restaurants, festivals, and religious buildings. If continuity and coherence are considered important aspects of place, clearly neither applies to mongrel cities.

Nevertheless, in all this hybridity, in multi-centred lives, in restless mobility, in displacement of all types, there seems to be one constant. The places where people come from and grew up remain locked in memories that inform subsequent place experiences. In short, in the words of psychoanalyst Elena Liotta, who comes from Argentina but lives in Italy, “the beginnings hold everything.”

This text from an installation in Victoria, British Columbia, captures well the sense that the beginnings hold everything, especially the phrase: “Our ways live both with and within us, and cannot be displaced.”

An unusual, combined expression of electronic media and mobility in the present age. Cell phone relays and a billboard for an travel clothing company in Toronto.

Electronic Media, the Global Village and an Electronic Sense of Place Electronic media permeate almost all place experiences of the present day. There was a recognition of the potentially pervasive effects of these in the 1960s with Marshall McLuhan’s suggestion that they shrink the world into a global village filled with immediate and undigested gossip about places that were once considered remote. But since the 1980s personal computers, the internet, mobile phones and social media have turned this suggestion into an continuous, omnipresent reality. It has been suggested that electronic media completely undermine sense of place, or rendered it obsolete, but a more nuanced argument is that in just a few decades they have reinforced the changes to place experiences associated with increased mobility because, as Sharon Kleinman suggests, they provide “nearly seamless anytime, anyplace connectivity” in which “here and there can be almost anywhere, and, moreover, both can be moving.” It is not exactly that a sense of local place has been destroyed but that an electronic sense of place has turned it into an elusive component of topological networks that connect it with a wider world.

Non-Place communities and an electronically poisoned sense of place There is another more ominous aspect to the impact of electronic media on place. They have made it easy for non-place (i.e. geographically scattered) communities of like-minded individuals to use social media to reinforce what they regard as the distinctive, exclusive and superior qualities of their place. Social media provide echo chambers for otherwise unrelated individuals to share prejudices and exacerbate the sorts of exclusionary convictions that arise whenever populations develop excessively protective attitudes about their neighbourhood, or their nation. This is an electronically poisoned sense of place that challenges the positive place effects and appreciation of diversity that arise from increased mobility, multi-centred living, and mongrel cities.

Comment As with changes that have happened to the character of places in the last fifty years, the changes that have happened to place experiences have had mixed consequences. In some ways they have reinforced place, in others they have reinforced placelessness, and sometimes they appear to do both simultaneously. They have broadened sense of place, changed it in ways that are still far from clear (especially in the case of electronic media), yet also amplified some its most unpleasant, parochial aspects. In the third post about changes to place I will offer some theoretical comments about how to understand these implications, and what they might bode for the future of place.

Marc Augé 1995 Non-Places: introduction to the anthropology of supermodernity, (London: Verso)

Tim Cresswell 2006 On the Move: mobility in the modern western world (London: Routledge), see p.257 about Schiphol

Sharon Kleinman 2007 Displacing place: mobile communication in the twenty-first century (New York: Peter Lang)

Elena Liotta 2009 On Soul and Earth: the psychic value of place (London: Routledge)

Lucy Lippard 1997 The Lure of the Local: senses of place in a multi-centered society, (New York: W.W.Norton)

Stephanie Taylor 2010 Narratives of identity and place (London: Routledge)