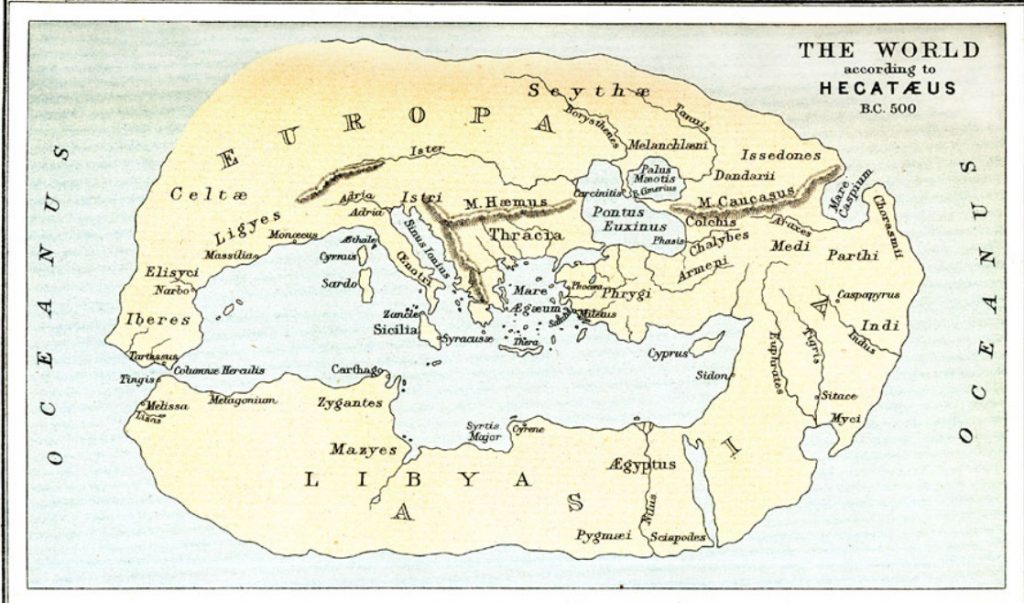

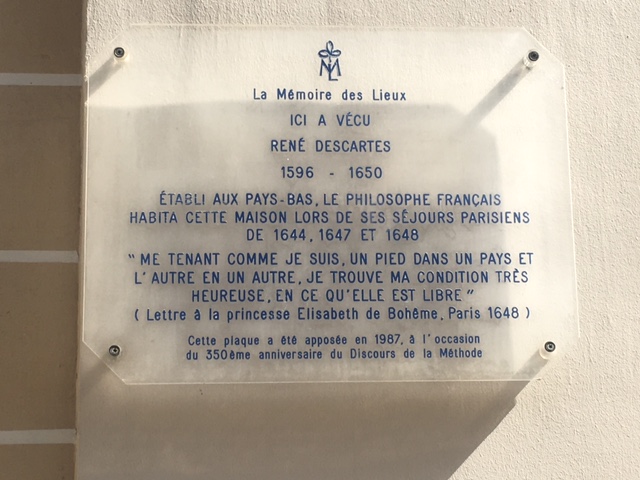

About a year ago I came upon a sign in Paris about Rene Descartes (shown below) that led me to wonder if place might have had some role in facilitating the insights of philosophers and scientists. I began to read biographies and autobiographies of some of them with whose work I was modestly acquainted, to see whether they suggest anything of note about the role of place in their lives. Understandably those books deal mostly with intellectual history, and many convey nothing of interest, but some offer intriguing though brief comments about the places where ideas where conceived or developed. This post is a sort of experiment based on just ten cases to see if the biographies of famous philosophers and scientists suggest anything of value about place.

Settled in the low countries, the French philosopher lived in this house for his stays in Paris 1644, 1647 and 1648.

“Having one foot in one country, and the other in another, I find my situation to be a happy one in in that it is free” (Letter to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, Paris 1648).

This plaque was mounted in 1987 on the 350th anniversary of Discourse on the Method.

René Descartes (1596-1650)

In Discourse on the Method of Reason Descartes developed an approach that lies at the foundation of rationalism and modern science. His method was, in his words, “never to accept anything as true that I did not incontrovertibly know to be so; carefully to avoid both prejudice and premature conclusions; and to include nothing in my judgements other than that which presented itself to my mind so clearly and distinctly, that I would have no occasion to doubt it.” From the perspective of place Discourse on the Method of Reason is significant because it includes clear descriptions of the places where Descartes formulated this method (though it’s important to note he concluded paradoxically that it led to the conviction that he himself “was a substance whose whole essence or nature is simply to think, and which doesn’t need any place or depend on any material thing.”)

In 1619 while he was returning to his position as an officer in the army of the Duke of Bavaria he was unexpectedly held up, probably somewhere near Munich, by the onset of winter, and it was then that his philosophical reflections began. “Finding no conversation to help me pass the time,” he wrote,” and no cares to trouble me, I stayed all day shut up alone in small room heated by a stove where I was free to talk with myself about my own thoughts.”

His life then immediately took a different turn, and he set aside his reflections for nine years when he “did nothing but roam from place to place, trying to be a spectator rather than an actor.” When he finally was about to settle in France it became clear that his scientific views were likely to be repressed by the Catholic church, so he moved to Holland, a Puritan country, where he could continue to develop his method of reason without fear of reprisals. In his words, he decided “to move away from all the places where I might have acquaintances and to retire here, in a country in which … people enjoy the fruits of peace with correspondingly greater security, and where amid a teeming, active, great people that shows more interest in its own affairs than curiosity for those of others, I have been able to live as solitary and as retiring a life as I would in the most remote of deserts, while lacking none of the comforts found in the most populous cities.”

Descartes lived at a time when war and religious orthodoxy were almost constant companions of everyday life. It appears that what mattered most for him were not places attractive for aesthetic or social distinctiveness but rather places attractive primarily for what they were not, ones free of distractions and ideological prejudice that allowed him the opportunity to pursue his own thoughts as he chose.

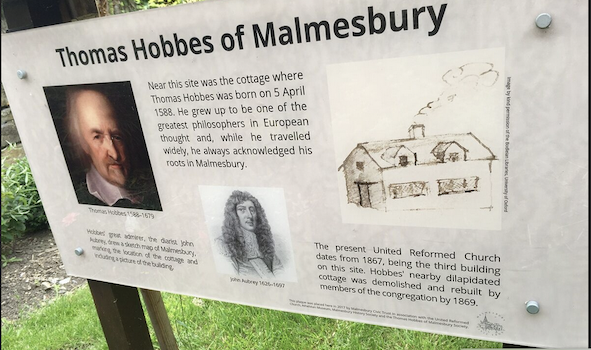

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

Hobbes, considered the founder of modern political philosophy, was a contemporary of Descartes, and they exchanged letters on a number of issues. The remarkable title page of his major work, Leviathan, shows the state as a monster comprised of the bodies of countless individuals, but it also identifies the author as “Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury.”

Malmesbury is the small town in Wiltshire in England where he was born and went to school, but to which he seems never to have returned. Leviathan was, in fact, written in Paris in the 1640s, where Hobbes had gone to escape the English civil war at the same time that Descartes was in the Netherlands avoiding the Catholic inquisition in France. Otherwise, place did not seem to play a role in his life.

Isaac Newton (1642-1727)

Newton was born at Woolsthorpe, a village in England, in 1642, at the beginning of the English Civil War. In 1664 he was a student studying classics at Cambridge when he came upon the works of Descartes and Galileo and, following their leads, his mind turned to science and mathematics. In the summer of 1665, the university was closed because of an outbreak of the plague, and he returned to Woolsthorpe to quarantine for almost two years. It was there that he made his initial experimental discoveries in optics and astronomy, and developed his understanding of mathematics, including the calculus, and and where he is said to have seen an apple falling from a tree that led him to the notion of gravity. In other words, rather like Descartes in the Netherlands and Hobbes in Paris, the important aspect of place for Newton was freedom from distracting concerns that allowed him time for contemplation, though in his case he found this at his familiar childhood home rather than a foreign country.

David Hume (1711-1776)

Hume was born and educated in Edinburgh, then moved to Bristol to work in business. He soon abandoned that and, as he wrote in his short autobiography My Own Life, “went over to France with a view of prosecuting my studies in a country retreat; and I there laid that plan of life, which I have steadily and successfully pursued…During my retreat in France, first at Reims, but chiefly at La Flèche, in Anjou, I composed my Treatise of Human Nature.” La Flèche was a small village where, whether coincidentally or not, Descartes had studied a century earlier. It provided the quiet and seclusion Hume initially wanted, but he soon moved to Paris. “There is,” he wrote, “a real satisfaction in living at Paris, from the great number of sensible, knowing, and polite company with which that city abounds above all places in the universe.”

Hume’s empirical approach to philosophy, that aimed to “reject every system … however subtle or ingenious, which is not founded on fact and observation”, explicitly influenced the work of Adam Smith, Immanuel Kant and Charles Darwin (who regarded it as a central influence on the theory of evolution).

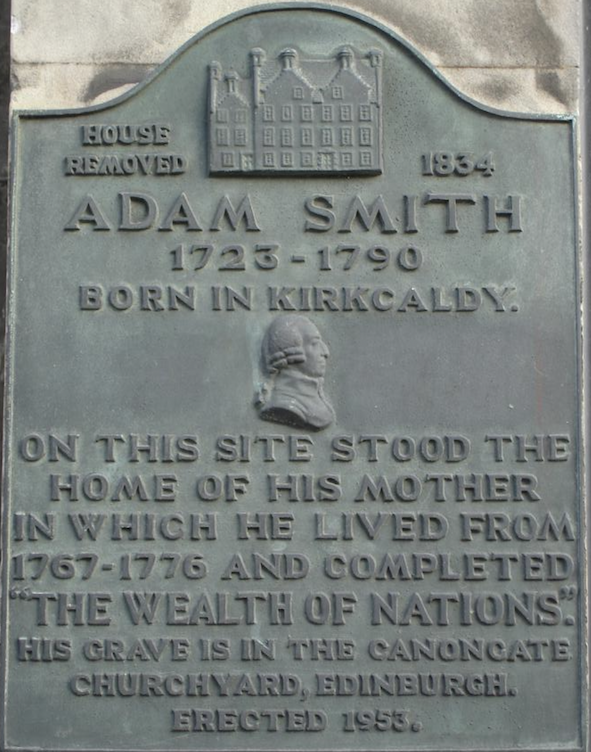

Adam Smith (1723-1790)

Adam Smith was born and went to school in the small town of Kirkcaldy near Edinburgh, then studied at the University of Glasgow and at Oxford (which he he found to be an intellectual desert compared with Glasgow). When he graduated he returned to Glasgow as a professor of moral philosophy and became deeply involved in the social life of the city, including with merchants and businessmen. These years he described afterwards as “by far the happiest, and most honourable period of my life.” But his university job paid poorly and after a few years he left for a higher paying position as tutor to a young English aristocrat. This took him to Toulouse in France (where, out of boredom he started work on The Wealth of Nations), and then to Paris, where David Hume introduced him to the intellectual society of the city, including social reformers (some called themselves les economistes) who had a very significant influence on his economic thinking.

When the person he was tutoring died unexpectedly, Smith returned to his mother’s house in Kirkcaldy to finish writing The Wealth of Nations. And apart from a few years in London around the time of his book’s publication in 1776, it was in Kirkcaldy that he lived most the rest of his life, eventually moving to Edinburgh where he died. So Smith’s life appears to have involved two contrasting experiences of place – the intense social and intellectual circles of Glasgow and Paris, and the quiet seclusion of his small home town.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

Kant is a key figure in modern philosophy because he both brought together the themes of early modern rationalism, and set the terms for most 19th and 20th century discussions. It was Hume’s work, he noted, that woke him from his “dogmatic slumber.” Kant lived in the small city of Koningsberg, then a major German commercial centre and port, now called Kaliningrad in Russia. Unlike most of his philosophical predecessors of the 17th and18th centuries, he spent his entire life in that one place. The reasons for his commitment to Koningsberg are not altogether clear. He constantly worried about his health, and may thought that travel would affect it adversely. He was also compulsively systematic, following exactly the routines every day, and it seems possible that he would have been unable to cope with the disruptions involved in moving to an unfamiliar place. Whatever the reason, he never traveled more than a few kilometres away from the city.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

Mill’s autobiographical essay is mostly devoted to his education, but gives hints about the importance of some places for his thinking. He was born in a suburb of London, and educated at home. There he met his father’s acquaintances, including utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham who had a house in the west of England where Mill spend a summer when he was about twelve and which he describes in his autobiography as “an important circumstance in my education.. a fine old place, so unlike the mean and cramped externals of English middle class life.” It was, he wrote in a statement that seems to anticipate his writing about liberty, somewhere that “gave the sentiment of a large and freer existence.”

A few years later, in his teenage years, he accompanied the Bentham family to France for several months, where he visited the Pyrenees, of which he wrote: “This first introduction to the highest order of mountain scenery made the deepest impression on me, and gave a colour to my tastes through life.” No less important was the fact that the trip included a visit to Paris where he was “exposed to continental liberalism” for the first time and started to become “a firm believer in the agency of the revolution – liberty, equality, fraternity.” France, and specifically “the enjoyment of country life” in the house he lived in near Avignon, became the place where he worked with his wife Harriet on many of the ideas of his seminal work On LIberty. After she died he made infrequent trips to England, and he was buried beside her in Avignon.

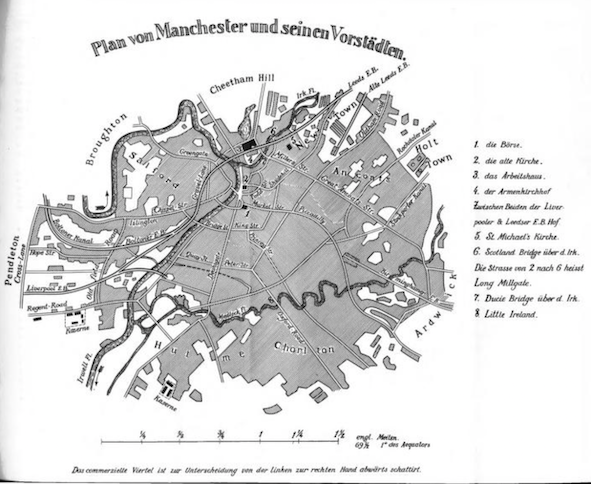

Friedrich Engels (1820-95)

The place experience of Engels, though more or less contemporary with that of Mills, could scarcely have differed more. He was born into a wealthy family of industrialists in what is now Wuppertal in Germany, and was sent to Manchester in 1842, when the city was by many accounts the epicentre of the industrial revolution, to supervise a cotton mill that was owned by his family. However, he had a radical view of the world, and as a keen observer of landscapes and places he systematically explored the city’s neighbourhoods, especially the poorest one. These he described in The Condition of the English Working Class in 1844 as a “planless, knotted chaos of houses, more or less on the verge of uninhabitableness.” In his book he described the poverty, filth and squalor, including families in single, windowless rooms, where many families lived “in defiance of all considerations of cleanliness, ventilation, and health.” The contrast with the clean and orderly areas where the middle classes lived could hardly have been greater. “When I consider in this connection the eager assurances of the middle-class, that the working-class is doing famously,” he wrote, “I cannot help feeling that the liberal manufacturers, the ‘Big Wigs’ of Manchester are not so innocent after all.”

This is the map of Manchester in the original 1845 German edition of Engels’ The Condition of the English Working Class. Engels did visit other industrial cities in England and found them no better than Manchester for their harsh differences between wealth and poverty, cleanliness and filth. It was his evocative descriptions of Manchester and those other places where these contrasts were so evident that attracted the attention of Karl Marx and led to their shared authorship of The Communist Manifesto.

Charles Darwin (1809-82)

Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, a small English city close to the mountains of North Wales where, in his youth, he frequently walked and appears to have developed his initial interest in the natural world. His formal education in Edinburgh and Cambridge he found “dull”, but his incidental interests in natural science, especially geology and etymology, led to his appointment in 1831 as a naturalist on the Beagle, a Royal Navy survey ship. In the five years of the voyage, which he described in his autobiography as “by far the most important event in my life,” he collected specimens and kept detailed notes about the natural history of all the places the Beagle visited in South America and elsewhere.

When the Beagle reached the Galapagos Islands his main focus was on their volcanic geology, and his field notes included only brief mentions of animals and plants. His autobiography, written towards the end of his life, describe the Islands as the place merely as important for their “singular relations of its plants and animals.” He had no epiphany about evolution while he was there. But as the Beagle sailed on to Tahiti he examined the specimens that had been collected by himself and others from the different Galapagos Islands and noticed that similar birds from different islands, though related to species he had seen on the mainland of South America, had developed features that suggested they were different species. However, it was not until 1845, nine years after the Beagle had returned to England and he had had time to confirm his observations with ornithologists and the work of other naturalists, that he realized the importance of what he had observed. He wrote then in his Journal of Researches (p. 394): “I never dreamed that islands about 50 or 60 miles apart, and most of them in sight of each other, formed of precisely the same rocks, placed under a quite similar climate, rising to a nearly equal height, would have been differently tenanted… It is the fate of most voyagers, no sooner to discover what is most interesting in any locality, than they are hurried from it…”

From the perspective of place Darwin’s life was a contrast between mobility and stability. A few years after the voyage of the Beagle he began to suffer from chronic illnesses (which he described as involving violent shivering and vomit attacks) that made both travel and social activities almost impossible. The most important place for him then became his house at Down, in the countryside south of London. In his autobiography he wrote: “We found this house and purchased it. I was pleased with the diversified appearance of vegetation proper to a chalk district, and so unlike what I had been accustomed to in the Midland counties; and still more pleased with the extreme quietness and rusticity of the place.” It was a retreat where he could concentrate on his scientific work when he was feeling well enough. “Few persons can have lived a more retired life than we have done. Besides short visits to the houses of relations, and occasionally to the seaside or elsewhere, we have gone nowhere.”

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855)

Kierkegaard is generally regarded as the first existential philosopher. He was a contemporary of Darwin and Engels, but his experiences of place had no similarity to either of theirs. He lived most of his life in Copenhagen within a one kilometre radius of Copenhagen’s Vor Frue Kirke (Church of Our Lady) and his place experience involved a complicated relationship with that city. “I regard the whole of Copenhagen as a great party,” he wrote. “But on one day I regard myself as the host who goes and talks to all the many invitees, my dear guests; on the next day I imagine that it is some great man who is giving the party and I am a guest.”

George Pattison has written that the city of Copenhagen is no less important a part of the background to Kierkegaard’s authorship than any intellectual and cultural movement. It was a crucial part of his writing process because he formulated his thoughts by walking around the city and talking with people, then wrote as soon as he returned to his house. Its streets, churches, parks, entertainments, and burial grounds were integral to the very fabric of his his critique of modernity and struggle to redefine what it meant to be Christian. Kierkegaard was a sort of flaneur for whom the place where he lived was replete with the meanings and attitudes of the age. His task deciphering those meanings made him increasingly dismayed about the degree to which belief and faith had been displaced by false convictions and rationalism. He began to refer to the city as “a market town” occupied by a “human swarm” and and to seek specific places, such as the Church of our Lady and the countryside outside the city, where he could be free of its influences and find inner peace.

A Concluding Comment

On the basis of these biographical summaries I think no firm conclusion can be drawn about the role of place in stimulating profound thinking and insights of notable philosophers and scientists.

For Descartes and Hobbes finding places free from ideological oppression was important. Newton’s innovative thinking seems to have benefitted from being quarantined at home. Hume, Mill and Smith were intellectually stimulated by life in Paris. but to write The Wealth of Nations Adam Smith presumably found it advantageous to live with his mother in his home town. Places encountered through travel were important to some, especially Darwin of course, though he, too, needed a quiet home place to write about those. Engels was an acute observer of places, and his radical ideas were stimulated by the inequality he saw in them. Kant lived his life in one place but it had no apparent role in his thinking. Kierkegaard also spent his life in one place but his experiences there were essential to his thinking .

In short, while associations with particular places were not unimportant in their lives, those associations took diverse and inconsistent forms. T

The Impact of Philosophers and Scientists on Places

The most notable relationships between philosophers and places, as indeed with many famous people, is actually in posterity. The various places where they were born, lived, studied and died have been given some lasting recognition, usually in plaques, signs and statues, sometimes by turning their houses into heritage sites. The site of the house in Malmesbury where Hobbes was born has a simple sign. So does the site of the long-demolished house in Kirkcaldy where Adam Smith spent most of life. Mill’s grave in Avignon has a decorative fence, and there’s a statue of him in London where he lived and worked for many years. Trip Advisor ranks the statue of Immanuel Kant as #37 of 238 things to do in Kaliningrad.

On a more elaborate scale the University of Glasgow has an Adam Smith Business School, an Adam Smith chair of Political Economy, an Adam Smith building, an Adam Smith Research Foundation and an Adam Smith Library. Newton’s estate in Woolsthorpe is now owned by the National Trust and, in some process of scientific place transference, grafts from the apple tree have been shipped to universities around the globe. Down House in Kent where Darwin lived is owned by English Heritage whose website recommends it as “A Great Value Family Day Out for Just £41.60”; the Galapagos Islands are marketed as an important destination for environmental tourists. Copenhagen has Søren Kierkegaard walking tours. Engels had largely been ignored In Manchester until 2017 when the rock musician Phil Collins got a statue of Engels he had found abandoned in Ukraine installed in front of the HOME performing arts centre.

I am not sure why identifying or visiting a place associated with a person famous should be considered worthwhile, though I often do it myself. Perhaps it is a way for us to admire and recall famous individuals, but I suspect we also quietly hope that by going to those places some of their insights or abilities will somehow rub off on us and we can share a little bit of their fame.

Darwin’s Down House as promoted on the website of English Heritage in 2023, and rubbing the toe of the statue in Edinburgh of David Hume, a person who did not believe in miracles, in the hope that it will bring good fortune.

References

• A general source I have found informative for this post is the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which has excellent biographies of philosophers and essays about their contributions to philosophy. Available at https://plato.stanford.edu

• René Descartes, Discourse on the Method trans Ian MacLean, Oxford World Classics, 2006 https://docslib.org/doc/10835580/descartes-1637-discourse-on-method-pdf

• David Hume, 1777, My Own Life, available at https://davidhume.org/texts/mol/

• John Stuart Mill, Autobiography available at https://www.utilitarianism.com/millauto/

• Friedrich Engels, 1845, The Condition of the English Working Class in 1844, available at https://archive.org/details/conditionworkingclassengland/page/49/mode/2up?view=theater

• Charles Darwin, 1881, The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2010/2010-h/2010-h.htm

• Charles Darwin, 1845, Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Countries visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, available at http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F14&viewtype=text&pageseq=1

• Kierkegaard – I have relied on George Pattison, 2013, “Kierkegaard and Copenhagen” in J. Lippet and G Pattison (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Kierkegaard, Oxford University Press. Available at https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/34339/chapter-abstract/327336322?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false

[Note: I have not included the philosopher Martin Heidegger in this post because because he is a sole exception to general disconnection between place and philosophical or scientific insight and because I have written about elsewhere in this website about his thinking, for instance in the posts Home and Place, and the Politics of Place.]

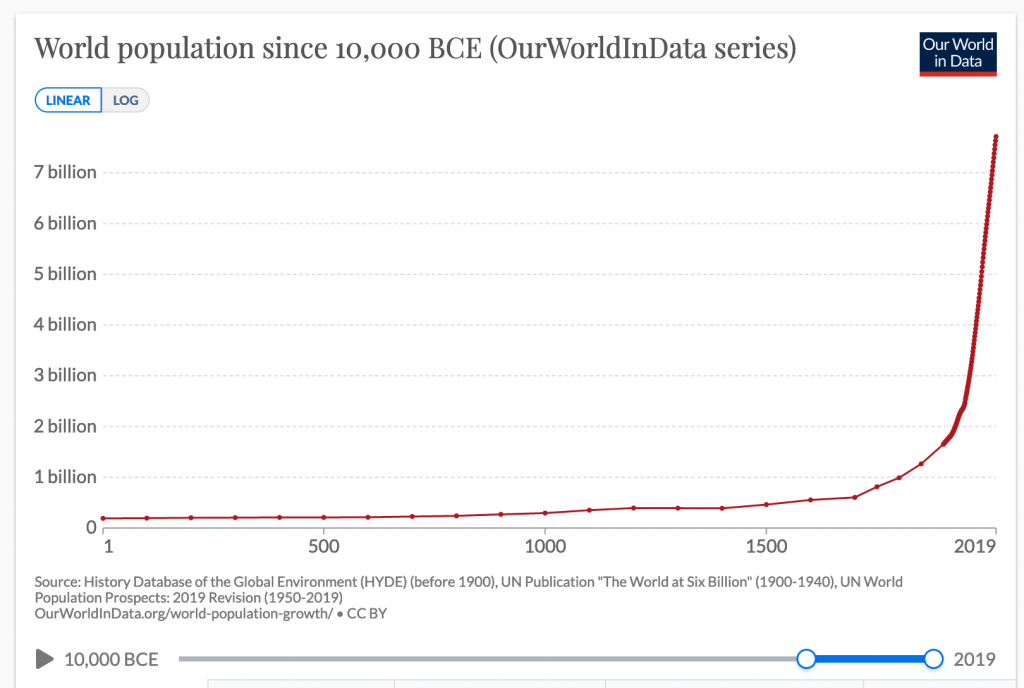

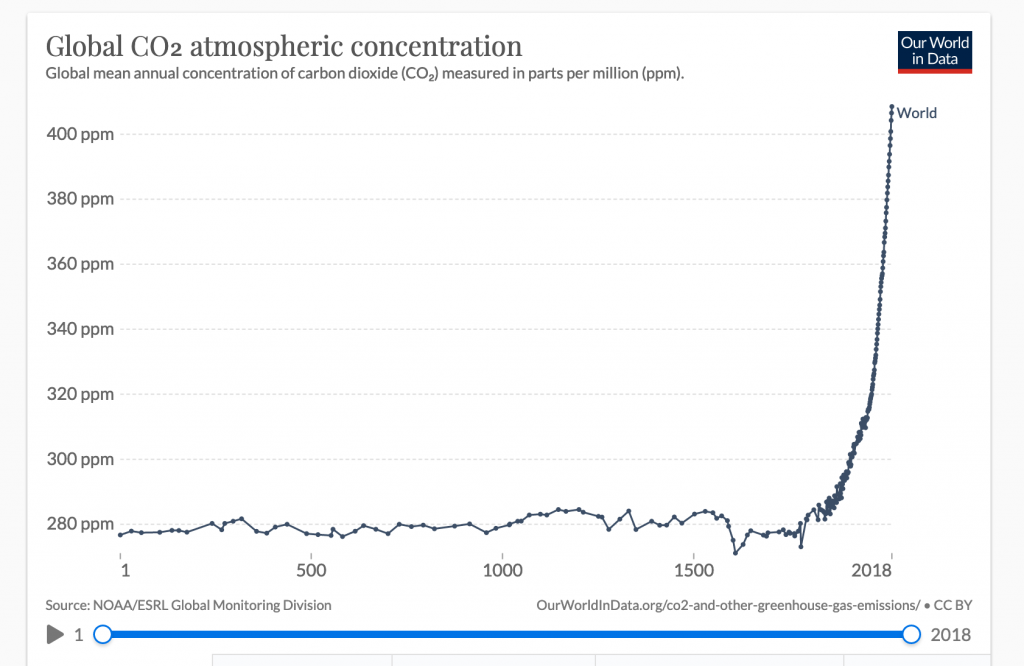

These shifts are the context for

These shifts are the context for