A nature reserve near Rice Lake in Southern Ontario protects a remnant of the tall grass prairie that once extended across much of the region.

Every place, no matter whether it is wild, rural or urban, has an ecosystem. And ecosystems, rather like places, extend across a range of scales from woodlots to the entire planet. This post is a summary of publications that reflect diverse ideas about the ecology of place, beginning with the importance of place for site-based field ecologists, then considering the ecology of imagination, and suggestions about ecology in place-based planning and environmental management. References are at the end.

Place for Ecologists

The chapters in The Ecology of Place: Contributions of Place-Based Research to Ecological Understanding, edited by Ian Billick and Mary Price (2010), are written by ecologists who have spent much of their research career working in specific places. In this they are not unlike many other field scientists – geomorphologists, biogeographers, botanists, entomologists – who can spend years investigating natural processes in a small area.

In the introduction to their book Billick and Price write: “We reserve ‘place’ to represent all of those idiosyncratic ecological features – including spatial location and time period – that define the ecological context of a field study.” They emphasize that the ecology of place assigns to the idiosyncrasies of place, time and taxon, a central and creative role in both the design and the interpretation of research. In other words, place is not a problem to be overcome or circumvented. It is a source of invaluable information that requires deep understanding of organisms and processes in a specific setting, and is something to be celebrated .

Another nature reserve in Southern Ontario – a restored marshland on the migratory route of terns, and the type of place that is deeply familiar to local ecologists as well as birders. For conservation purposes ecology is necessarily place specific.

Nevertheless most science publications do not encourage place-based accounts, and favour research that deals with the diversity, complexity and contingency of ecological systems by searching for broad patterns, or uses empirical data to test theories about general processes. However, the contributors to Billick and Price’s book argue that the results of place-based research are rarely parochial and the ecological specifics of a place contribute invaluable insights to general scientific understanding about ecological processes. In short, specific place research and general scientific explanations are complementary rather than incompatible.

In one of the chapters D.M. Waller and S. Flade claim that: “Aldo Leopold’s land ethic is…grounded in both ecological understanding and love of place.” It seems that Leopold’s work serves as an inspiration for many of those writing about the ecology of place, especially his observation that the motivation for conserving the ecological health of the land, and the knowledge of how to do this, arises from deep personal involvement in the natural history of a particular place. In their conclusion Billick and Price suggest that it is this motivational power of place that draws ecologists back to their specific field sites year after year, and that this power has the capacity to draw citizens and scientists together in the collaborative effort needed to solve environmental problems.

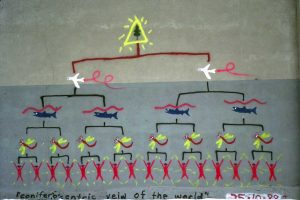

An imaginative ecological grafitto (photographed in 1988, now long gone) in Toronto titled “The Coniferocentric Veiw of the World” shows a conifer at the apex, with birds (looking like planes, then fish and dragonflies, and what I think are people at the base.

The Ecology of Imagination

Edith Cobb’s remarkable book on The Ecology of Imagination (1977) is an indirect reinforcement of the motivational power of place. For her the ecology of imagination has to do with “the genius of childhood”, by which she means the spontaneity and creative imagination of children in the their relationships with nature. “Experience in childhood,” she writes, “is never formal or abstract… the world of nature is not a ‘scene’, nor even a landscape. Nature for the child is sheer sensory experience.” An experience that combines the cultural and the natural, self and world.Cobb suggests that the ecology of imagination implicated in this nature-mind-body-society continuum is actually a phenomenon of evolution at bio-cultural levels, a phenomenon that begins with the natural genius of childhood and the spirit of place. Although the character of individual experiences in the ecology of childhood imagination can influence environmental attitudes for the rest of a person’s life, it is the case, that with maturity the child (which is to say all of us) effectively evolves out of nature into culture and “experience of environment becomes thought about environment.” I don’t doubt the general truth of this, but I do think that the essays in Billick and Price’s book indicate that at least for place-based ecological scientists the motivational power of the ecology of place is never lost.

This also may be the case for others who seek to uncover the imaginative ecology of place. For instance, Carl Lavery and Simon Whitehead are respectively a theatre scholar and a professional dancer who meet regularly in West Wales to discuss shared interests in place, ecology and embodiment. They draw in part on a critical reading of Heidegger’s ideas about dwelling in order to develop what they call “an ecology of place performance research” (2012). Whitehead says: “As I see it, home doesn’t start with language, as it does in (Lavery’s) explanation of Heidegger, it starts with the body. The body is an amazing ecological resource…In a sense, the body is the first home, and the place or territory where you live is the second home.” Ecology, he suggests, teaches that everything is connected and brings into question the whole of subjectivity and capitalistic power. Place has specificity yet is relational. It is part of network in which, as in ecology, everything is connected. These qualities he then attempts to disclose through dance and in works of performance art.

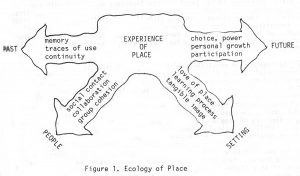

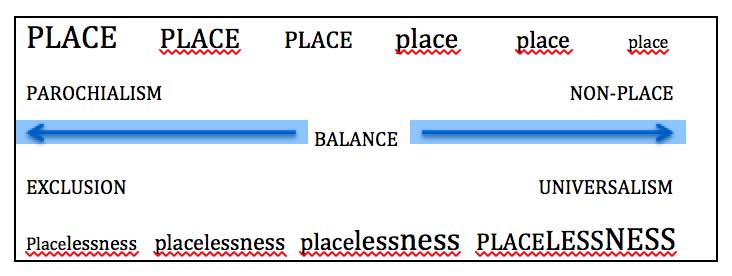

Kim Dovey’s diagram of the Ecology of Place, from his 1988 publication.

Ecology, Place, Design and Planning.

An altogether more prosaic understanding of the ecology of place regards it as an approach that can lead sustainable, healthy plans and designs for urban development. Kim Dovey, (a leading contributor in a books and essays to ideas about place and design), wrote a paper in 1985 about the ecology of place and placemaking in which he claimed that: “The more we understand of the concept and meanings of place…the more we realize the interdependencies of people, form and meaning.” His diagram indicates that what he understood by ecology was primarily the interaction of social processes rather than natural ones, an indication reinforced by his propositions for making what he called “healthy places” with a self-sustaining dynamism. These propositions include: Embodying an emotional connection; Bringing people together; Creating a tangible image and distinctive character; Acknowledging both constant change and connections with the past and the future.

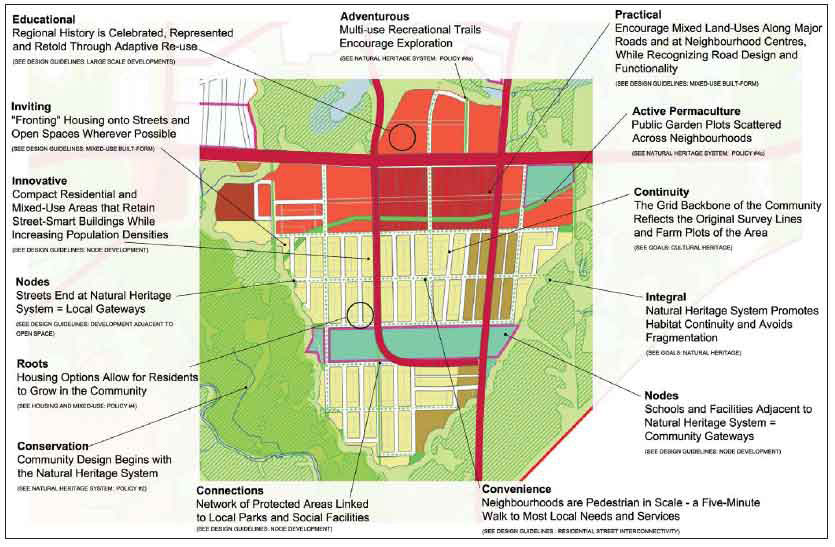

A rather different interpretation is offered approach is provided by Beatley and Manning in The Ecology of Place (1997). They offer a “vision” of how we might plan for places (which means built/urban places) by attending to the interconnections of ecological and social processes. They draw especially on the ideas of Ian McHarg, a landscape architect, about designing with, rather than against, nature, attending to natural cycles, minimizing waste and resource demands, greening cities, building community resilience, and studying the character of the bioregion. They are especially critical of low-density, environmentally damaging urban sprawl, and regard the ecology of place as a foundation for the types of sustainability and environmentally sensitive design approaches that are advocated in new urbanism. These approaches, they argue, offer a vision of a future in which land is used sparingly, landscapes are cherished and cities are compact, vibrant and green. “This vision of place emphasizes both the ecological and social, where quantity of consumption is replaced with quality of relationships.”

The ecology of place in urban planning. This diagram is of a proposed new town called Seaton that may be built to the east of Toronto. It is designed to protect the existing valleys, promote habitat continuity, include permaculture, and general respond to and celebrate the ecology of the site.

Home Place and Parochial Ecology

If it could be widely applied this ecological approach to urban development might allay the concerns of Stan Rowe, an environmentalist from the Canadian prairies, who, in his book Home Place: Essays on Ecology (1990), argues that in cities the instinctive sense of ourselves as related ecologically to the land has slipped away. Though he writes about many local places, Rowe’s ‘home place’ is actually Gaia, the Earth as an ecosphere, and his book is a plea for environmental awareness that echoes Leopold’s call for a land ethic. He concludes his book dramatically the statement that the “Human history will end in ecology, or nothing.”

Michael Northcott is a theologian with, I think, not dissimilar views. In his recent book Place, Ecology and the Sacred (2015) he invokes Leopold’s notion of “land pathology” (which is similar to Rowe’s concern about the ecological blindness of city life) and argues that the loss of sense of place, which he thinks began about 1800 with industrialization and industrial agriculture, is central to the modern ecological crisis. The thrust of his book is that the sense of the sacred that emanates from local communities of faith in Christian and Jewish tradition amounts to what he calls a “parochial ecology.” In pre-modern ages this was a powerful force, and if it can be rediscovered it might again be the foundation for creating places that are “politically just, economically productive and ecologically sustainable.” He writes that: “Places of dwelling become places, and indeed sacred places, as they are shaped by human experience in interaction with local and specific ecological qualities.”

Comment

The books I mention here are, as far as I am aware, the most substantial and explicit ones about the ecology of place. There are not many of them and they offer a striking range of interpretations. While I like to hope that the place-based ecological arguments of Beatley and Manning, Dovey, and Northcott might have some influence on future place-making and place-adaptation, intellectually what I find most important are Edith Cobb’s ideas about the ecology of imagination in childhood, and the demonstration in Billick and Price’s book that place-based research can involve emotional attachments to places without compromising scientific integrity. The great majority of writing about place is about human-made places. They are excellent reminders that every place is part of a nature-mind-body-society continuum and that the nature part should not be overlooked.

History will end in ecology. A dead oak tree on a farm estate near Ludlow in Shropshire, England that supplies the nearby Ludlow Food Centre, where locally grown foods are sold.

References

Beatley, T. and Manning K. 1997 The Ecology of Place: Planning for Environment, Economy and the Community, Island Press

Billick, I. and Price, M.V. (eds) 2010 The Ecology of Place: Contributions of Place-Based Research to Ecological Understanding, University of Chicago Press

Cobb, Edith, 1977 The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood, Columbia University Press

Dovey, K. 1985 “An Ecology of Place and Placemaking” 93-109, in Dovey, K., Downton, P, Missingham, G (eds) Place and Placemaking, Proceedings of Paper 85 Conference, Melbourne.

Lavery, Carl, and Whitehead, Simon 2012 “Bringing it all back home: Towards an Ecology of Place” Performance Research 17(4), 111-119

Northcott, Michael S. 2015 Place Ecology and the Sacred: The Moral Geography of Sustainable Communities, Bloomsbury Press

Rowe, Stan, 1990 Home place : essays on ecology NeWest Press

Distinctiveness pushed to the extreme results in parochialism, exclusionary attitudes, even ethnic cleansing. Such attitudes have to be regarded not just as narrow-minded but as naïve in a world now interconnected by electronic communications, air travel and intermittent epidemics of emergent and other diseases. They will not keep out the next flu pandemic nor protect against tidal surges and ideas communicated on the Internet.

Distinctiveness pushed to the extreme results in parochialism, exclusionary attitudes, even ethnic cleansing. Such attitudes have to be regarded not just as narrow-minded but as naïve in a world now interconnected by electronic communications, air travel and intermittent epidemics of emergent and other diseases. They will not keep out the next flu pandemic nor protect against tidal surges and ideas communicated on the Internet.